As you know, we entered our discussion of derivatives to determine the size and direction of a step with which to move along a cost curve. We first used a derivative in a single variable function to see how the output of our cost curve changed with respect to change a change in one of our regression line's variables. Then we learned about partial derivatives to see how a three-dimensional cost curve responded to a change in the regression line.

However, we have not yet explicitly showed how partial derivatives apply to gradient descent.

Well, that's what we hope to show in this lesson: explain how we can use partial derivatives to find the path to minimize our cost function, and thus find our "best fit" regression line.

You will be able to:

- Define a gradient in relation to gradient descent

Now gradient descent literally means that we are taking the shortest path to descend towards our minimum. However, it is somewhat easier to understand gradient ascent than descent, and the two are quite related, so that's where we'll begin. Gradient ascent, as you could guess, simply means that we want to move in the direction of steepest ascent.

Now moving in the direction of greatest ascent for a function

Note how this is a different task from what we have previously worked on for multivariable functions. So far, we have used partial derivatives to calculate the gain from moving directly in either the

Here, in finding gradient ascent, our task is not to calculate the gain from a move in either the

$x$ or$y$ direction. Instead, our task is to find some combination of a change in$x$ ,$y$ that brings the largest change in output.

So if you look at the path our climbers are taking in the picture above, that is the direction of gradient ascent. If they tilt their path to the right or left, they will no longer be moving along the steepest upward path.

The direction of the greatest rate of increase of a function is called the gradient. We denote the gradient with the nabla, which comes from the Greek word for harp, which is kind of what it looks like:

Now how do we find the direction for the greatest rate of increase? We use partial derivatives. Here's why.

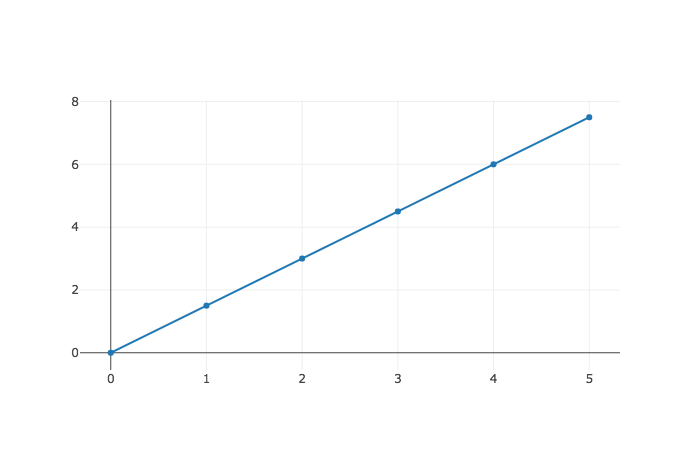

As we know, the partial derivative

Let's relate this again to mountain climbers. Imagine the vertical edge on the left is our y-axis and the horizontal edge is on the bottom is our x-axis. For the climber in the yellow jacket, imagine his step size is three feet. A step straight along the y-axis will move him further upwards than a step along the x-axis. So in taking that step, he should direct himself more towards the y-axis than the x-axis. That will produce a bigger increase per step size.

In fact, the direction of greatest ascent for a function,

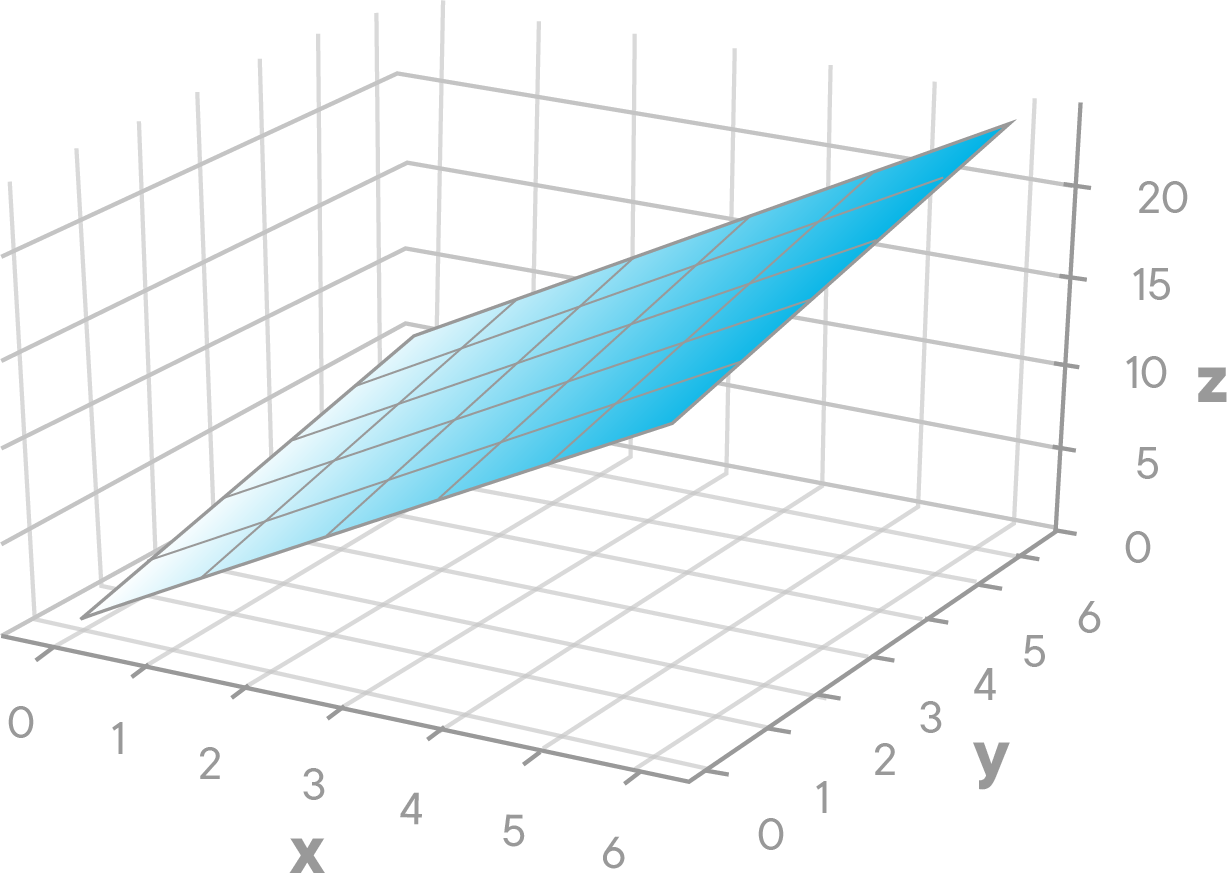

Now that we have a better understanding of a gradient, let's apply our understanding to a multivariable function. Here is a plot of a function:

Imagine being at the bottom left of the graph at the point

The gradient of the function

$\frac{df}{dx}(2x + 3y) = 2 $ and

So what this tells us is to move in the direction of greatest ascent for the function

So this path maps up well to what we see visually. That is the idea behind gradient descent. The gradient is the partial derivative with respect to each type of variable of a multivariable function, in this case

In this lesson, you saw how to use gradient descent to find the direction of steepest descent. You saw that the direction of steepest descent is generally some combination of a change in your variables to produce the greatest negative rate of change.

You first how saw how to calculate the gradient ascent, or the gradient

For gradient descent, that is to find the direction of greatest decrease, you simply reverse the direction of your partial derivatives and move in $ - \frac{\delta f}{\delta y}, - \frac{\delta f}{\delta x}$.