The goal of this project is to implement a program that can read a disk or partition image with a supported filesystem and display its contents, some filesystem information, etc.

Important

To understand the implementation details and the program in general, you are expected to have at least basic knowledge of the filesystem and partition table structure.

If you are not familiar with these concepts, consider reading the References section.

- C++ compiler: preferably

GCC(version 12.3.0 or higher) CMake(version 3.15 or higher)boost::program_options(version 1.76.0 or higher)fmt(version 8.1.1 or higher)e2fsprogs(version 1.46.5 or higher)

Note

For installation instructions, please refer to the official documentation.

Use the provided CMakeLists.txt to compile the project:

cmake -S . -B build -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release && cmake --build build --parallel./fs_reader <image_file> [options]Where:

<image_file>is the name of the image file to read[options]is a list of options to pass to the program

Here is a table of supported options:

| Option | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

-h, --help |

Display help message | Overrides all other options |

-i, --image |

Specify image file to read | Can be also specified as a positional argument |

-s, --superblock |

Display superblock information | |

-r, --root |

Display root directory contents | |

-R, --recursive |

Display directory contents recursively | Requires -r or --root option |

-j, --journal |

Display journal information | Requires filesystem with journaling enabled |

-t, --transactions |

Display transactions list | Requires filesystem with journaling enabled |

-p, --partition |

Specify partition number to read | Only valid for disk images, i.e. images with partition table |

-P, --partitions |

Display partition table | Overrides all other options except -h and --help. Only valid for disk images |

Note

If no options are specified, the program will only display the superblock validity and filesystem type.

The program supports the following filesystems:

ext2ext3 (with journal support)ext4 (with journal support)

Also, the following partition tables are supported:

MBR (including extended partitions)GPT

Both filesystems and partition tables are detected automatically.

Tip

If you are trying to read a partition image, you should specify the -p option.

In order to determine the partition number, please refer to the output of the -P option.

Also note that MBR extended partitions cannot be read directly. You should specify the logical partition inside the extended partition.

Warning

Do not rely on output of other utilities, such as fdisk, parted, etc. to determine the partition number,

as they may differ in interpretation of partition table data.

In order to test the program, you will need a disk or partition image with a supported filesystem.

For your convenience, we've provided a scripts that can create such images for you automatically. Please refer to the scripts/README.md for more information.

Note

Alternatively, you can use our ready-made images. For the sake of size, they are not included in the repository, but you can download them from this repository.

This repository contains multiple images with different filesystems and partition tables for testing purposes.

- Support for

ext2/ext3/ext4filesystems - Journal support for

ext3/ext4filesystems - Support for

MBRpartition tables (including extended partitions) - Support for

GPTpartition tables - Automatic detection of filesystem type and partition table type

- Recursive directory listing

The program structure can be divided into the five main parts: image dumping, reading partition table, filesystem reading and detection, content listing and journal reading. Let's take a closer look at each of them.

Before the filesystem can be read, the image file should be mapped into virtual address space of the program.

The responsibility to do so lies on the ImageDump class. Then, shared pointers to the ImageDump object

are used throughout the project to access the image data. This approach allows us to avoid unnecessary copying of the image data.

Note

All methods, structures and classes related to the image dumping are located in the inc/disk_image and

src/disk_image directories.

The PartitionTable class is responsible for reading the partition table from the image.

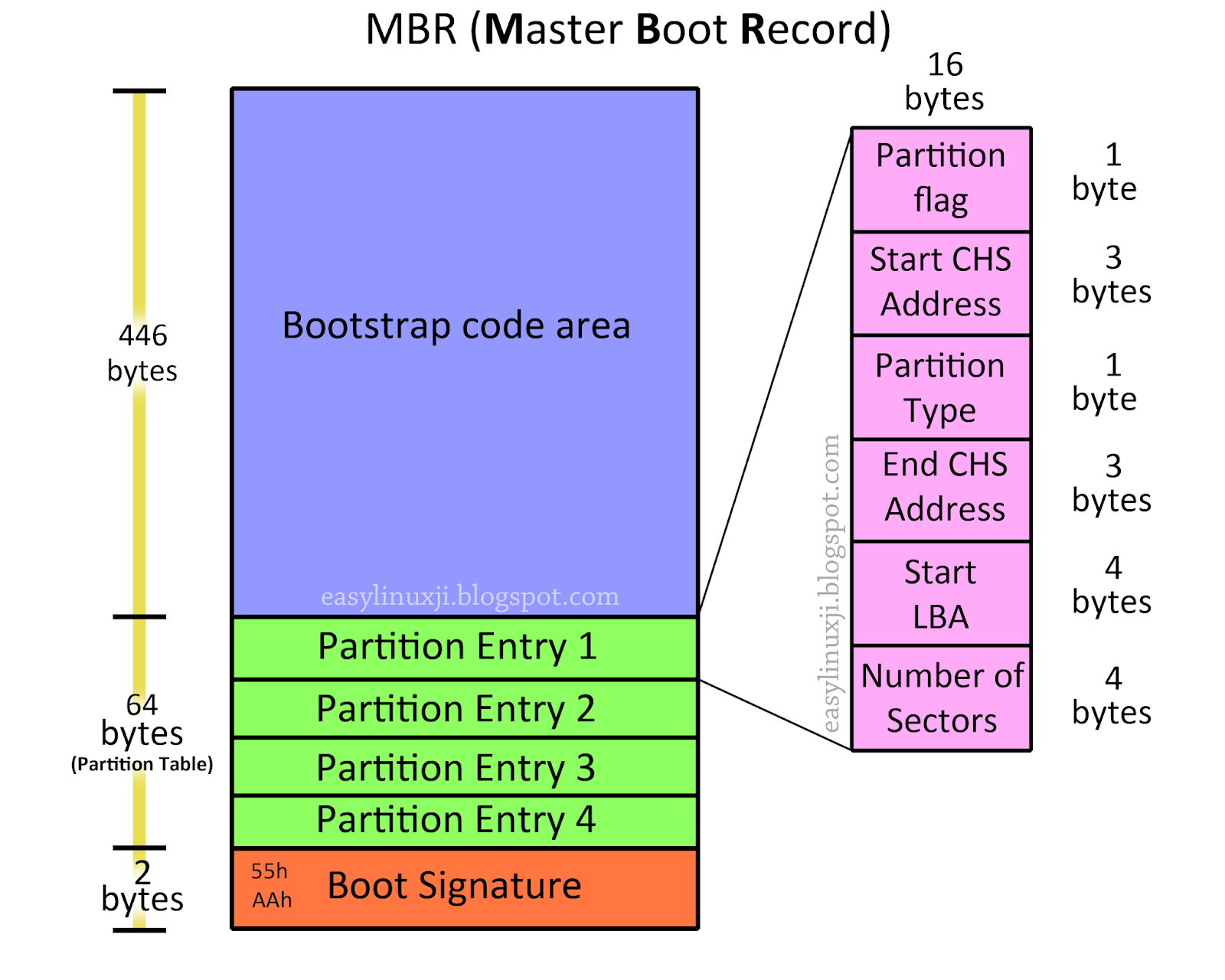

The first step is to read the Master Boot Record (MBR) from the image. The MBR is located in its first sector.

The MBR contains the partition table itself, as well as the boot code and the disk signature. If

the latter is present and valid, the type of the first partition of MBR is checked to determine the partition

table type. If the type is found to be 0xEE, the partitioning scheme is assumed to be GPT. Otherwise,

it is assumed to be MBR.

Important

If the disk signature is not present or invalid, the partition table reading step is skipped and the partition table is assumed to be absent.

Each partition is written into an internal vector of partitions. Each partition is represented either by

MBR::Partition or GPT::Partition class, depending on the partition table type.

Note

All methods, structures and classes related to the partition table are located in the inc/disk_image/structs and

src/disk_image/structs directories.

The reading of the MBR partition table is straightforward. Each Partition Table Entry (PTE) contains the following fields:

Partition flag- indicates whether the partition is bootableCHS address of first sector- the CHS address of the first sector of the partitionPartition type- the type of the partitionCHS address of last sector- the CHS address of the last sector of the partitionLBA of first sector- the LBA address of the first sector of the partitionNumber of sectors in partition- the number of sectors in the partition

The reader iterates over all PTEs and creates a MBR::Partition object for each of them.

The special case is the extended partition. It is a special type of partition that can contain multiple

logical partitions. The extended partition type is 0x05 in case of CHS addressing and 0x0F in case of LBA addressing.

The extended partition contains its own partition table, called Extended Boot Record (EBR) that precedes each logical partition. The EBR contains the same fields as the MBR, except only the first two PTEs are used. The first PTE is the logical partition itself, and the second one is the next EBR. The last EBR is filled with zeros.

Source: Wikipedia

The reader also iterates over all logical partitions and creates a MBR::Partition object for each of them.

The LBA of first sector field is later used to determine the offset of the partition in the image.

The GPT partitioning scheme is the modern replacement for the MBR. It is used on UEFI systems and supports larger disks and more partitions.

In case of GPT partitioning, the first sector of the image always contains the Protective MBR (PMBR), which is basically a dummy MBR that is kept untouched for backward compatibility. The UEFI specification requires that the PMBR partition table contain one partition record, with the other three partition records set to zero.

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

The first sector, which is equal to the LBA of first sector field of the first PTE, contains the GPT header.

This header contains the information about the partition table, such as the number of partitions, starting

LBA of the partition table, etc.

According to the LBA of the partition table, the reader reads the partition table itself. Each partition

is represented by the GPT::Partition class as stated above.

Note

All methods, structures and classes related to the filesystem are located in the inc/filesystem and

src/filesystem directories.

When disk image is loaded into memory and the partition table is parsed, the filesystem can be read.

User can specify the partition number to read using the -p option. If no partition number is specified,

the program will try to read the image as a single filesystem. In this case, if the image contains a partition table,

the program will fail with an error and print the available partitions for the user to choose from.

In any case, the FilesystemDump object is created from the image data, either from the whole image or

from the specified partition. To avoid unnecessary copying of the image data, the FilesystemDump object

uses the same shared pointer to the ImageDump object and stores the offset and size of the filesystem

in the image.

The FilesystemDump object is then used to construct the Filesystem object, which will be later used

by the FilesystemReader class to read it.

The Filesystem class represents the filesystem itself. It holds two main objects: FSInfo and Journal.

The journal will be discussed later, so let's take a look at the FSInfo class.

The FSInfo, as the name suggests, contains the information about the filesystem represented by the following

fields:

dump- theFilesystemDumpobject that was described abovesuper_block- the superblock of the filesystemblock_size- the size of the block in bytesdescriptor_table- the descriptor table of the filesystemtype- the type of the filesystem

The FSInfo class is separated from the Filesystem intentionally. This is needed for other parts of the program,

such as Inode, Superblock, Directory, etc. to be able to access the filesystem information without

creating unwanted circular dependencies between classes.

Here's a quick overview of these fields:

The superblock is the most important part of the filesystem. It contains all important information about it, such as the block size, the number of inodes, its state, features, etc.

The superblock is always located at the offset 1024 bytes from the beginning of the filesystem and takes

exactly 1024 bytes. The superblock is represented by the Superblock class.

The block size is determined by the superblock.

The descriptor table is a special structure used to define parameters of the filesystem block groups. It provides the location of the inode bitmap and inode table, block bitmap, number of free blocks and inodes, and some other useful information.

The descriptor table is always located in the first block after the superblock. This is important, as for example, on the filesystem with the block size of 1024 bytes, the group descriptor table will be located in the third block of the filesystem, while on the filesystem with the block size of 2048 bytes or more, it will be located in the second block.

The descriptor table is represented by the DescriptorTable class.

This part is kind of tricky. The problem is that the filesystem type is not stored anywhere in the image.

This is likely the outcome of the strong backward compatibility of the ext family of filesystems, as

it is possible to mount ext2 or ext3 filesystem as ext4. ext3 is even partially forward compatible

with ext4, making it possible to mount ext4 filesystem as ext3 after disabling some features.

This suggests to us that the filesystem type is effectively determined only by the features that are enabled for this particular filesystem. There is simply no other way to determine the filesystem type.

The filesystem type is determined using the following algorithm:

The default filesystem type is set to EXT2. If it has the EXT3_FEATURE_COMPAT_HAS_JOURNAL feature,

the filesystem type is set to EXT3, as well as if it has any other unsupported EXT2 features.

Finally, if the filesystem has any unsupported EXT3 features, the filesystem type is suspected to be EXT4.

Note

As there is no way to unequivocally determine the filesystem type, the detected filesystem type can be interpreted only as a suggestion for the user. The program itself always relies on the very specific features it depends on only.

This is the main part of the program. The FilesystemReader provides the interface for the user to

print the desired information about the filesystem or its contents.

We will focus on parsing the directory contents, as it is the most interesting part and actually the main task of this project.

The process of parsing the directory contents starts with creating the Directory object from the

root directory inode. In the ext family of filesystems, the root directory inode is always 2.

The directory entries are located in the data blocks of the directory inode.

The inode is represented by the Inode class. Inode provides its own InodeIterator to iterate

over the data blocks. Then, the DirectoryIterator is used to iterate over the directory entries

in the data blocks of the inode, incorporating the InodeIterator.

The directory entries are represented by the Dirent class.

Now, let's take a closer look at each of these classes and related principles.

The Inode class, as stated above, represents the inode of the filesystem. It mostly just wraps

the pointer to the inode in the filesystem dump and provides some useful methods to access the inode

metadata and its contents.

To find the inode in the filesystem dump, the following operations are performed:

- The inode number is converted to the inode index by subtracting 1 from it

- The inode index is divided by the number of inodes per group to get the group index

- To get the inode index inside the group, the inode index is divided by the number of inodes per group and the remainder is taken

- The offset of the inode inside the group is divided by the block size to get the block index inside the group

- To find the offset of the inode inside the block, the offset of the inode inside the group is divided by the block size and the remainder is taken

- The number of the block, containing the inode on the filesystem, is calculated by adding the block index inside the group to the inode table block number in the corresponding group descriptor table entry

- The address of the inode in the filesystem dump is then effectively determined by adding the inblock offset to the offset of the inode block in the filesystem dump

The data of inode can be stored in two ways: in the data blocks or as inline data. The latter is used for small files, while the former is used for larger files and directories. Inline data will be discussed later, so let's focus on the data blocks.

Depending on the filesystem features, the data blocks can be organized using different layouts.

If the inode has the EXT4_EXTENTS_FL feature, the data blocks are organized using the extent tree, otherwise

the data blocks are organized using the block tables.

In this case, the block layout is organized using the direct and indirect (up to 3 levels) block tables.

Source: University of Illinois at Chicago

The first 12 entries of the inode block table are direct block pointers. The 13th entry is a single indirect block pointer, the 14th entry is a double indirect block pointer, and the 15th entry is a triple indirect block pointer.

The conversion between the inode logical block number and the physical block number is performed by the Inode::logical_to_block method.

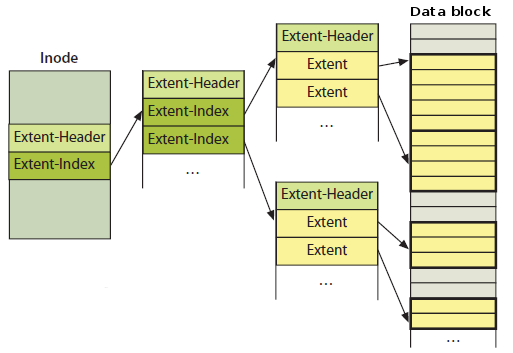

In this case, the block layout is organized using the extent tree.

The extent tree is a special tree structure used to store the data more efficiently.

It was introduced in ext4 to replace the block tables.

Extent itself is just a contiguous block of data, which is represented by the start block number and the number

of blocks in the extent.

Source: Data Recovery Tools

Each node of the tree begins with the extent header, which contains the number of entries and the depth of the node.

If the node is an interior node, the header is followed by the index entries, each of which points to the block

containing more nodes in the extent tree. If the node is a leaf node, the header is followed by the extent entries,

each of which points to the actual data blocks of the file. The root node of the extent tree is stored in the inode i_block field,

previously used for the block tables.

The conversion between the inode logical block number and the physical block number is performed by the Inode::extent_to_block method.

The inline data is stored directly in the inode itself. It was also introduced in ext4 to store small files more efficiently.

If the file is smaller than 60 bytes, the data are stored inline in the i_block field of the inode. Otherwise,

the data can also be stored in the extended attribute space of the inode under the system.data attribute.

If the data size exceeds the size of the extended attribute space, the separate data blocks are allocated.

The Inode class stores the inline data in the inline_data field internally. This field is populated

automatically when the Inode object is created if the inode has the EXT4_INLINE_DATA_FL feature.

Due to the nature of the inline data, it is not possible to iterate over it using the InodeIterator, so

all methods that access the inode data should first check the return value of the Inode::has_inline_data method

and use the Inode::get_inline_data method to access it.

The reading of the inline data is performed by the Inode::read_inline_data method.

The InodeIterator simply provides the convenient interface to iterate over the data blocks of the inode.

It automatically handles the block tables and extent tree, so the difference between them is not visible

to the user.

It also automatically skips the empty blocks, if any, which is crucial for the directory parsing. This, however, is not the case for the extent tree, as it does not contain empty blocks.

The Directory class represents the directory inode. It provides the interface to print the directory contents

and access the directory entries. The directory entries are represented by the Dirent class.

The Dirent is a simple wrapper around the ext2_dir_entry structure that provides a more convenient interface

for accessing the directory entry type, name, inode number, etc. It also provides the printing functionality.

The DirectoryIterator class is the most important part of the directory parsing. It provides the interface

to iterate over the directory entries in the data blocks of the directory inode.

A directory file is a linked list of directory entry structures. Each structure contains the name of the entry,

the inode associated with the data of this entry, and the distance within the directory file block to the next entry

in the list. The DirectoryIterator uses this distance to iterate over the directory entries within the data blocks,

incorporating the InodeIterator to iterate over the data blocks of the inode, if the directory entries do not fit

in a single data block, or uses the Inode::get_inline_data method to read the directory entries from the inline data.

Note

Using the standard linked list directory format can become very slow once the number of files starts growing.

To improve performance in such a system, modern filesystems use the indexed directory format, which allows

them to quickly locate the particular file searched.

However, we decided to stick with the standard linked list directory format for two reasons:

- It provides the most general approach to parsing the directory contents thanks to the backward compatibility. That said, it requires a small amount of code to implement, therefore making the overall structure easier to understand.

- In any case, our implementation is only intended to be used for parsing the entire directory contents recursively, so there will be no significant performance gain from using the indexed directory format.

The journal is a special part of the filesystem that is used to store the information about the filesystem changes before they are actually applied to the filesystem. This is needed to ensure the filesystem consistency in case of a system crash or power failure.

The journal is represented by the Journal class. It provides the interface to read the journal contents

and print the journal entries (transactions).

In this project, we do not aim to implement the journal replaying, so the journal is read-only.

The journal is located in the data blocks of the journal inode. The journal inode is determined by the s_journal_inum

field of the superblock. In most cases, it is equal to 8.

Important

All fields of the journal are stored in the big-endian byte order, as opposed to the little-endian byte order

used by the rest of the filesystem. Due to this, there is a special swap_endian function that is used

to swap the endianness of the journal fields. It can be found in the inc/utils/utils.h file.

Note

All methods, structures and classes related to the journal are located in the inc/filesystem/journal and

src/filesystem/journal directories.

Each journal block is preceded by the journal block header, which determines the type of the following block.

The journal block header is represented by the JournalBlockHeader class.

The first block of the journal inode is the journal superblock,

which contains the information about the journal, such as the journal UUID, journal features, etc.

The journal superblock is represented by the JournalSuperblock class.

The rest of the blocks are used to store the transactions.

The descriptor block contains an array of journal block tags that describe the final locations of the data blocks that follow in the journal. Descriptor blocks are open-coded instead of being completely described by a data structure.

Note

The journal block tags structure and size depend on the journal features. There is a special function

that is used to determine the size of the journal block tags structure with respect to the journal features:

journal_tag_bytes.

The journal descriptor block is represented by the JournalDescriptorBlock class. It provides the interface

to iterate over the journal block tags, which are represented by the JournalBlockTag class.

To iterate over the journal block tags, the DescBlockIterator class is used. It incorporates the journal_tag_bytes

function to determine the offset to the next journal block tag. It also correctly handles to open-coded

UUID fields, the presence of which depends on JBD2_FLAG_SAME_UUID flag of the tag. The last tag in the descriptor

block is indicated by the JBD2_FLAG_LAST_TAG flag.

The commit block is a sentry that indicates that a transaction has been completely written to the journal. Once this commit block reaches the journal, the data stored with this transaction can be written to their final locations on disk.

The commit block is represented by the JournalCommitBlock class. It is a simple wrapper around the commit_header

structure and provides the interface to access the transaction sequence number and the transaction commit time.

The combination of the descriptor blocks, data blocks, and commit block is called a transaction. The Journal

class provides the interface to get the transaction list from the filesystem journal. It works as follows:

- The

Journalclass reads the journal superblock and determines the journal features - Then, it iterates over the blocks of the journal inode, keeping track of the current transaction

- If the current block is a descriptor block, the

Transactionobject is filled with the data from the journal block tags, incorporating theDescBlockIteratorclass - If the current block is a commit block, the

Transactionobject is marked as complete, the timestamp, and the sequence number is set, the transaction is added to the transaction list, and the current transaction is reset - Repeat steps 3–4 until the end of the journal inode is reached

The transaction itself is represented by the Transaction class. It provides the interface to access necessary

transaction information and contains the following fields:

timestamp- the transaction commit timesequence- the transaction sequence numberblocks- the list of the blocks that were modified by this transaction

Each block is represented by the Transaction::block structure. It contains the following fields:

fs_block- the filesystem block numberj_block- the journal block numberflags- the flags of the block (not used)

Tip

The transaction list can be displayed using the -t option.

Also, the -j option can be used to display the journal superblock information.

Knowing that, let's take a look at the example output of the -t option:

Transactions:

FS Block J Block Timestamp Sequence

83 -> 2 Mon Dec 4 20:37:56 2023 2

85 -> 3 Mon Dec 4 20:37:56 2023 2

83 -> 6 Mon Dec 4 20:38:02 2023 3

85 -> 7 Mon Dec 4 20:38:02 2023 3

81 -> 8 Mon Dec 4 20:38:02 2023 3

The first column is the filesystem block number modified by the transaction. The second column is the corresponding journal block number that contains the modified block. Timestamp and sequence number are self-explanatory.

This section contains a list of useful resources that were used during the development of this project.

- ext2 documentation (unofficial)

- ext4 documentation (unofficial)

- MBR Partition table

- GPT Partition table

This project is licensed under the terms of the MIT license.

Copyright © 2023 Andrii Yaroshevych, Anastasiia Shvets