A(rbitrarily) C(ompilable) I(mprovement) D(irectory), or ACID for short (thanks Bob), is a structure for creating super metroid hacks which implements many large scale system and subsystem changes/rewrites that I wrote while working on Project Base 0.8. The hack released in 2020, but the codebase needed to be heavily refactored before making it ACID, so the new codebase wasn't completed until much later, and now it is finally available here on github.

- My formatting, specifically with tabs and spaces, has been messed up by uploading it to github. It doesn't change anything in the code functionality of course, but much of the formatting now looks inconsistent with itself, and with the way I structure whitespace in my code as a general rule.

- I intend to finish commenting large portions of the codebase, but for the time being I think it's more useful to have it available to view and utilize.

- I have more plans for this codebase for the future, but it is complete enough as it is that I think it can be of some use to people currently.

- I have tried to credit everyone whose code has influenced or been used in any part to create this, in the code comments themselves (and the credit sheets for project base), but if you think I forgot to credit you for something in the codebase, please let me know.

- This codebase is made for use with the compiler Xkas0.6. There may be syntax that would need to be changed for another snes compiler like Asar. I wanted to make the most of xkas and smile2.5, so there was not much done to make it comptabile with tools that automatically find free space or do anything similar. I plan to one day make this compatible with Asar and SMART, but until then people are free to make an asar version themselves

1. main.asm contains a structured ram map with clear and easy to use variable names for most of the important addresses in the game.

It also brings all the different parts of the codebase together, so the only thing you have to do is compile main.asm onto the rom. In that respect, it is comparable to a header file. This file also contains a set of bit flag arrays that act as configuration flags for the whole code base. These flags control whether many of the included features are active in the game, not active at all, or able to be activated. Or in item terms, acquired vs equipped vs not acquired.

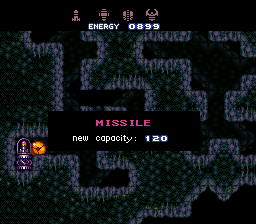

Put simply, the message box system in Super Metroid kinda sucks. It's a little clever in how it renders the text box (the way it uses hdma to move the layer in pieces away from the centre) and how it calculates the size and locations from the header list, but ultimately it was not made in a very modular or expandable way whatsoever. So, I designed an entirely new one, that is still based on the general design of the original game (similar to what I did to the subscreen). Not only does this new message box system make adding new messages in all kinds of different ways much more simple, but it implements a form of String Substitution, which you may be familiar with from higher level languages. Specifically, this substitution system (using the common symbol %+X followed by the pointers in paranthasese after the text to denote a substitution within the text) allows for several types of things you can insert in to a message. It does of course support the what the original game did by less dynamic means, those being button icons and simple graphics. However it can also insert functions, which have the ability to show dynamic information, as well as options in the form of words that can be selected and chosen as an answer (see: Yes/No for save game). The potential of these substitutions is huge, with the message boxes being able to support a large (all things considered) number of any combination of these substitutions. It also makes drawing graphics for them much easier, with a substitution being a pointer to the tilemap in a format consistent with the rest of the codebase. Other new features include the ability to define the gfx set being loaded for the message box, the required length open, and even the border gfx.

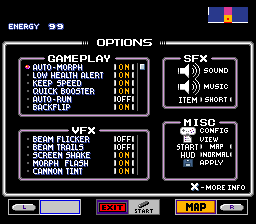

The codebase implements a system of options controlled by an array of bitflags similar to the event bits already in the game. These options can control various functions of the game by adding a function call with the option bit as the argument, but the ones already implemented include options for accessability such as turning off the screen shake effect, beam flicker, speed echoes, adding an auto run, auto save, etc. These options can be controlled by the player if the creator desires, by implementing them in game through the subscreen or a custom display. They can also be controlled pre-compilation from the header file.

This is something that has gone through many iterations, and is still not fully complete (a few certain block types still do not get recognized), but is in a state where it feels quite polished and viable for other hacks. It is based on various games, but primarily it was inspired by the simple ledge grab and morph system in am2r, as well as the extremely limited auto-morph in Redesign: Axiel Edition. Unlike Redesign however, this implementation of an automatic morph function acts as a natural extension of the original physics engine, being incorporated directly into the collision detection routines. As such, it requires Zero input from the hack creator to function. It does not need special block types to define where it activates like redesign, and is far more robust and expandable than am2r’s system. Not only does Auto-morph act on it’s own in a logical way when it encounters a morph-able location (and can be turned on/off through an option bit), but it does so by creating a bitmap (small array of bits representing block interaction) of the blocks around the player, and then compares that directly to predefined patterns. The reason these patterns are pre-defined is so that a hack creator can change, remove, or even add, patterns to tailor auto-morph exactly the way they want it, without having to alter the fundamental collision detection and reaction code that makes it run.

This is a big one. I have made many different HUD’s for Super Metroid, but ultimately, they were specific to the hack they were used in, and despite having interesting features, they were not something conducive to using this code as a base for different hacks. I wanted to design a HUD that could be useful to people of every skill level. From someone who has never touched assembly code, to someone who can make their own HUD. No other HUD code I have seen in Super Metroid is anything like this. So I decided to completely redesign the way the HUD is rendered from the ground up. The end result is a HUD that is completely modular, without losing any significant performance over the entirely hard coded HUD of the original game. The ACID HUD system allows for HUD’s to be created in any combination of the different widgets people are used to having in a hack, and quite a few other new ones too (like a display that accurately shows the animation frame to achieve a quick charge, which similar in game displays do not do as accurately). This modularity goes as far as to support being edited in real time in game (see: video on my youtube channel) if the HUD is run from RAM instead of ROM (a fairly simply change to the provided code). To make it perform as well as possible compared to the extremely efficient hardcoded original HUD, it uses a system of bitflags representing whether a particular widget needs to update at any point. This is implemented in such a way that on any given frame, only one or two widget ever needs to run update code. This means that over a series of frames, on average, it uses little to no extra processing compared to the original. This performance of course depends on the needs of the particular widgets (input tracking widgets for example use more performance, but even those uses mirror memory addresses and some extra work to make them rarely slower), but over all it is at times even faster, and at worst only a little slower, than a hard coded HUD. The other aspect of this HUD is of course creating the arrangement of widgets, which can currently be done quickly and easily in ASCII using the provided python script, but which could easily be turned into a graphical interface (one day I will make time to design one myself) as well. On top of that, there are provided widgets for most things, but for anyone who wants to make their own, it is very easy to add widgets as they follow a consistent object structure

This is included under extras because it was designed for Project Base, but it can be used for any other hack as well. It is definitely the most complex addition, and also probably the most clever coding. Door transitions are a symphony of timing and clever programming around the way a CRT draws a frame, but they had a shortcoming. They were not designed around door transitions being faster, or in slightly different configurations. In the original game, it only creates a visual glitch on a handful of occasions, and they are hard to notice even then. However, I was determined to make door transitions not only support much faster scrolling, but even smoother movement by allowing the screen to fade as the door aligns itself with the centre of the screen. Doing this was not simple, and required writing a new colour fade routine that can run during an IRQ interrupt by ensuring the cycles taken fit within a budget given to each of the functions that need to run to handle the movement during a transition. As well as of course writing a new door transition game state structure, among other things. They are very smooth now.

This is the other really big one. Subscreens (map, equipment screen) in Super Metroid are more or less hard coded. The ‘less’ part is where I based an entirely new subscreen system on. For project base, I needed to make a subscreen system that felt like the natural extension of the general structure of the original, which seems almost designed to support arbitrary subscreens, but never implemented that functionality. So, I wrote a new one that not only implements arbitrary extra subscreens in an easy to work with and understand structure, but it also supports a new subsystem for rendering lists of options instead of hard coding those lists like the original equipment screen. In other words, I wrote a GUI toolkit for running subscreens so that I could implement my own version of the equipment screen for project base, as well as design an options screen for changing everything from button configuration to visual effects, the hud, sound effects, and more. This part of the code base is not commented the way I want it to be, and I will add a full explanation of how it works and how to use it, but for now I hope it is easy enough to figure out based on what I did comment.