Short, simple, direct scripts for creating character-based graphs in a command terminal. Status: stable. Features added very rarely.

To generate graphs directly in the (ASCII-based) terminal. Most common use-case:

if you type long | list | of | commands | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn in the terminal,

then you could replace the final | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn with | distribution and

very likely be happier with what you see.

The tool is mis-named. It was originally for generating histograms (a distribution of the frequency of input tokens) but it has since been expanded to generate time-series graphs (or, in fact, graphs with any arbitrary "x-axis") as well.

At first, there will be only two scripts, the originals written in Perl and Python by Tim Ellis. Any other versions people are willing to create will be placed here. The next likely candidate language is C++.

There are a few typical use cases for graphs in a terminal as we'll lay out here:

A stream of ASCII bytes, tokenize it, tally the matching tokens, and graph the result. For this example, assume "file" is a list of words with one word per line, so passing it to "xargs" makes it all-one-line.

$ cat file | xargs #put all words on one line

this is an arbitrary stream of tokens. this will be graphed with tokens pulled out. this is the first use case.

$ cat file | xargs | distribution --tokenize=word --match=word --size=small -v

tokens/lines examined: 25

tokens/lines matched: 21

histogram keys: 17

runtime: 8.00ms

Key|Ct (Pct) Histogram

this|3 (14.29%) -----------------------------------------------------------------------o

is|2 (9.52%) ---------------------------------------o

tokens|2 (9.52%) ---------------------------------------o

graphed|1 (4.76%) -------o

will|1 (4.76%) -------o

An already-tokenised input, one-per-line, tally and graph them.

$ cat file | distribution -s=small -v

tokens/lines examined: 21

tokens/lines matched: 21

histogram keys: 18

runtime: 14.00ms

Key|Ct (Pct) Histogram

this|3 (14.29%) -----------------------------------------------------------------------o

is|2 (9.52%) ---------------------------------------o

graphed|1 (4.76%) -------o

be|1 (4.76%) -------o

A list of tallies + tokens, one-per-line. Create a graph with labels. This matches the typical output of several Unix commands such as "du."

$ du -s /etc/*/ 2>/dev/null | distribution -g -v

tokens/lines examined: 107

tokens/lines matched: 5,176

histogram keys: 107

runtime: 2.00ms

Key|Ct (Pct) Histogram

/etc/ssl/|920 (17.77%) -------------------------------------------

/etc/init.d/|396 (7.65%) -------------------

/etc/apt/|284 (5.49%) -------------

/etc/nagios-plugins/|224 (4.33%) -----------

/etc/cis/|188 (3.63%) ---------

/etc/nagios/|180 (3.48%) ---------

/etc/fonts/|172 (3.32%) --------

/etc/ssh/|172 (3.32%) --------

/etc/default/|164 (3.17%) --------

/etc/console-setup/|132 (2.55%) -------

A list of tallies only. Create a graph without labels. This is typical if you just

have a stream of numbers and wonder what they look like. The --numonly switch is

used to toggle this behaviour.

There is a different project: https://github.com/holman/spark that will produce simpler, more-compact graphs. By contrast, this project will produce rather lengthy and verbose graphs with far more resolution, which you may prefer.

- Configurable colourised output.

- rcfile for your own preferred default commandline options.

- Full Perl tokenising and regexp matching.

- Partial-width Unicode characters for high-resolution charts.

- Configurable chart sizes including "fill up my whole screen."

If you use homebrew, brew install distribution should do the trick, although

if you already have Perl or Python installed, you can simply download the file

and put it into your path.

To put the script into your homedir on the machine you plan to run the script:

$ wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/philovivero/distribution/master/distribution.py

$ sudo mv distribution.py /usr/local/bin/distribution

$ alias worddist="distribution -t=word"

It is fine to place the script anywhere in your $PATH. The worddist alias is

useful for asking the script to tokenize the input for you eg ls -alR | worddist.

--keys=K periodically prune hash to K keys (default 5000)

--char=C character(s) to use for histogram character, some substitutions follow:

pl Use 1/3-width unicode partial lines to simulate 3x actual terminal width

pb Use 1/8-width unicode partial blocks to simulate 8x actual terminal width

ba (▬) Bar

bl (Ξ) Building

em (—) Emdash

me (⋯) Mid-Elipses

di (♦) Diamond

dt (•) Dot

sq (□) Square

--color colourise the output

--graph[=G] input is already key/value pairs. vk is default:

kv input is ordered key then value

vk input is ordered value then key

--height=N height of histogram, headers non-inclusive, overrides --size

--help get help

--logarithmic logarithmic graph

--match=RE only match lines (or tokens) that match this regexp, some substitutions follow:

word ^[A-Z,a-z]+$ - tokens/lines must be entirely alphabetic

num ^\d+$ - tokens/lines must be entirely numeric

--numonly[=N] input is numerics, simply graph values without labels

actual input is just values (default - abs, absolute are synonymous to actual)

diff input monotonically-increasing, graph differences (of 2nd and later values)

--palette=P comma-separated list of ANSI colour values for portions of the output

in this order: regular, key, count, percent, graph. implies --color.

--rcfile=F use this rcfile instead of $HOME/.distributionrc - must be first argument!

--size=S size of histogram, can abbreviate to single character, overridden by --width/--height

small 40x10

medium 80x20

large 120x30

full terminal width x terminal height (approximately)

--tokenize=RE split input on regexp RE and make histogram of all resulting tokens

word [^\w] - split on non-word characters like colons, brackets, commas, etc

white \s - split on whitespace

--width=N width of the histogram report, N characters, overrides --size

--verbose be verbose

You can grab out parts of your syslog ask the script to tokenize on non-word delimiters, then only match words. The verbosity gives you some stats as it works and right before it prints the histogram.

$ zcat /var/log/syslog*gz \

| awk '{print $5" "$6}' \

| distribution --tokenize=word --match=word --height=10 --verbose --char=o

tokens/lines examined: 16,645

tokens/lines matched: 5,843

histogram keys: 92

runtime: 10.75ms

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

ntop |1818 (31.11%) ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo

WARNING |1619 (27.71%) ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo

kernel |1146 (19.61%) ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo

CRON |153 (2.62%) ooooo

root |147 (2.52%) ooooo

message |99 (1.69%) ooo

last |99 (1.69%) ooo

ntpd |99 (1.69%) ooo

dhclient |88 (1.51%) ooo

THREADMGMT|52 (0.89%) oo

You can start thinking of normal commands in new ways. For example, you can take your "ps ax" output, get just the command portion, and do a word-analysis on it. You might find some words are rather interesting. In this case, it appears Chrome is doing some sort of A/B testing and their commandline exposes that.

$ ps axww \

| cut -c 28- \

| distribution --tokenize=word --match=word --char='|' --width=90 --height=25

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

usr |100 (6.17%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

lib |73 (4.51%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

browser |38 (2.35%) ||||||||||||||||||||

chromium |38 (2.35%) ||||||||||||||||||||

P |32 (1.98%) |||||||||||||||||

daemon |31 (1.91%) |||||||||||||||||

sbin |26 (1.60%) ||||||||||||||

gnome |23 (1.42%) ||||||||||||

bin |22 (1.36%) ||||||||||||

kworker |21 (1.30%) |||||||||||

type |19 (1.17%) ||||||||||

gvfs |17 (1.05%) |||||||||

no |17 (1.05%) |||||||||

en |16 (0.99%) |||||||||

indicator |15 (0.93%) ||||||||

channel |14 (0.86%) ||||||||

bash |14 (0.86%) ||||||||

US |14 (0.86%) ||||||||

lang |14 (0.86%) ||||||||

force |12 (0.74%) |||||||

pluto |12 (0.74%) |||||||

ProxyConnectionImpact |12 (0.74%) |||||||

HiddenExperimentB |12 (0.74%) |||||||

ConnectBackupJobsEnabled|12 (0.74%) |||||||

session |12 (0.74%) |||||||

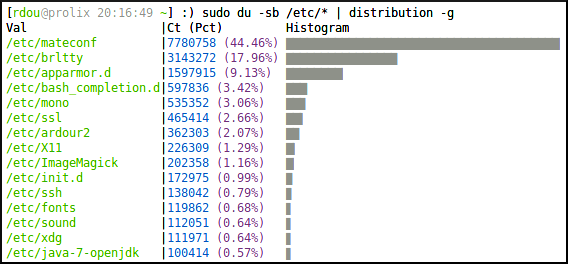

Sometimes the output you have is already some keys with their counts. For example the output of "du" or "command | uniq -c". In these cases, use the --graph (-g) option, which skips the parsing and tokenizing of the input.

Further, you can use very short versions of the options in case you don't like typing a lot. The default character is "+" because it creates a type of grid system which makes it easy for the eye to trace right/left or up/down.

$ sudo du -sb /etc/* | distribution -w=90 -h=15 -g

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

/etc/mateconf |7780758 (44.60%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

/etc/brltty |3143272 (18.02%) ++++++++++++++++++++

/etc/apparmor.d |1597915 (9.16%) ++++++++++

/etc/bash_completion.d|597836 (3.43%) ++++

/etc/mono |535352 (3.07%) ++++

/etc/ssl |465414 (2.67%) +++

/etc/ardour2 |362303 (2.08%) +++

/etc/X11 |226309 (1.30%) ++

/etc/ImageMagick |202358 (1.16%) ++

/etc/init.d |143281 (0.82%) +

/etc/ssh |138042 (0.79%) +

/etc/fonts |119862 (0.69%) +

/etc/sound |112051 (0.64%) +

/etc/xdg |111971 (0.64%) +

/etc/java-7-openjdk |100414 (0.58%) +

The output is separated between STDOUT and STDERR so you can sort the resulting histogram by values. This is useful for time series or other cases where the keys you're graphing are in some natural order. Note how the "-v" output still appears at the top.

$ cat NotServingRegionException-DateHour.txt \

| distribution -v \

| sort -n

tokens/lines examined: 1,414,196

tokens/lines matched: 1,414,196

histogram keys: 453

runtime: 1279.30ms

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

2012-07-13 03|38360 (2.71%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++

2012-07-28 21|18293 (1.29%) ++++++++++++

2012-07-28 23|20748 (1.47%) +++++++++++++

2012-07-29 06|15692 (1.11%) ++++++++++

2012-07-29 07|30432 (2.15%) +++++++++++++++++++

2012-07-29 08|76943 (5.44%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

2012-07-29 09|54955 (3.89%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

2012-07-30 05|15652 (1.11%) ++++++++++

2012-07-30 09|40102 (2.84%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++

2012-07-30 10|21718 (1.54%) ++++++++++++++

2012-07-30 16|16041 (1.13%) ++++++++++

2012-08-01 09|22740 (1.61%) ++++++++++++++

2012-08-02 04|31851 (2.25%) ++++++++++++++++++++

2012-08-02 06|28748 (2.03%) ++++++++++++++++++

2012-08-02 07|18062 (1.28%) ++++++++++++

2012-08-02 20|23519 (1.66%) +++++++++++++++

2012-08-03 03|21587 (1.53%) ++++++++++++++

2012-08-03 08|33409 (2.36%) +++++++++++++++++++++

2012-08-03 10|15854 (1.12%) ++++++++++

2012-08-03 15|29828 (2.11%) +++++++++++++++++++

2012-08-03 16|20478 (1.45%) +++++++++++++

2012-08-03 17|39758 (2.81%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++

2012-08-03 18|19514 (1.38%) ++++++++++++

2012-08-03 19|18353 (1.30%) ++++++++++++

2012-08-03 22|18726 (1.32%) ++++++++++++

__________________

$ cat /usr/share/dict/words \

| awk '{print length($1)}' \

| distribution -c=: -w=90 -h=16 \

| sort -n

Val|Ct (Pct) Histogram

2 |182 (0.18%) :

3 |845 (0.85%) ::::

4 |3346 (3.37%) ::::::::::::::::

5 |6788 (6.84%) :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

6 |11278 (11.37%) ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

7 |14787 (14.91%) :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

8 |15674 (15.81%) ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

9 |14262 (14.38%) :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

10|11546 (11.64%) :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

11|8415 (8.49%) :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

12|5508 (5.55%) :::::::::::::::::::::::::

13|3236 (3.26%) :::::::::::::::

14|1679 (1.69%) ::::::::

15|893 (0.90%) :::::

16|382 (0.39%) ::

17|176 (0.18%) :

You can sometimes gain interesting insights just by measuring the size of files on your filesystem. Someone had captured slow-query-logs for every hour for most of a day. Assuming they all compressed the same (a proper analysis would be on uncompressed files - uncompressing them would have caused server impact - this is good enough for illustration's sake), we can determine how much slow query traffic appeared during a given hour of the day.

Something happened around 8am but otherwise the server seems to follow a normal sinusoidal pattern. But note because we're only analysing the file size, it could be that 8am had the same number of slow queries, but that the queries themselves were larger in byte-count. Or that the queries didn't compress as well.

Also note that we aren't seeing every histogram entry here. Always take care to remember the tool is hiding low-frequency data from you unless you ask it to draw uncommonly-tall histograms.

$ du -sb mysql-slow.log.*.gz | ~/distribution -g | sort -n

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

mysql-slow.log.01.gz|1426694 (5.38%) ++++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.02.gz|1499467 (5.65%) +++++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.03.gz|1840727 (6.94%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.04.gz|1570131 (5.92%) ++++++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.05.gz|1439021 (5.42%) ++++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.07.gz|859939 (3.24%) ++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.08.gz|2976177 (11.21%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.09.gz|792269 (2.99%) +++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.11.gz|722148 (2.72%) ++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.12.gz|825731 (3.11%) ++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.14.gz|1476023 (5.56%) +++++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.15.gz|2087129 (7.86%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.16.gz|1905867 (7.18%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.19.gz|1314297 (4.95%) +++++++++++++++++++

mysql-slow.log.20.gz|802212 (3.02%) ++++++++++++

A more-proper analysis on another set of slow logs involved actually getting the time the query ran, pulling out the date/hour portion of the timestamp, and graphing the result.

At first blush, it might appear someone had captured logs for various hours of one day and at 10am for several days in a row. However, note that the Pct column shows this is only about 20% of all data, which we can also conclude because there are 964 histogram entries, of which we're only seeing a couple dozen. This means something happened on July 31st that caused slow queries all day, and then 10am is a time of day when slow queries tend to happen. To test this theory, we might re-run this with a "--height=600" (or even 900) to see nearly all the entries to get a more precise idea of what's going on.

$ zcat mysql-slow.log.*.gz \

| fgrep Time: \

| cut -c 9-17 \

| ~/distribution --width=90 --verbose \

| sort -n

tokens/lines examined: 30,027

tokens/lines matched: 30,027

histogram keys: 964

runtime: 1224.58ms

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

120731 03|274 (0.91%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 04|210 (0.70%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 07|208 (0.69%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 08|271 (0.90%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 09|403 (1.34%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 10|556 (1.85%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 11|421 (1.40%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 12|293 (0.98%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 13|327 (1.09%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 14|318 (1.06%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 15|446 (1.49%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 16|397 (1.32%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120731 17|228 (0.76%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120801 10|515 (1.72%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120803 10|223 (0.74%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120809 10|215 (0.72%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120810 10|210 (0.70%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120814 10|193 (0.64%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++

120815 10|205 (0.68%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++

120816 10|207 (0.69%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++

120817 10|226 (0.75%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

120819 10|197 (0.66%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++

A typical problem for MySQL administrators is figuring out how many slow queries are taking how long. The slow query log can be quite verbose. Analysing it in a visual nature can help. For example, there is a line that looks like this in the slow query log:

# Query_time: 5.260353 Lock_time: 0.000052 Rows_sent: 0 Rows_examined: 2414 Rows_affected: 1108 Rows_read: 2

It might be useful to see how many queries ran for how long in increments of tenths of seconds. You can grab that third field and get tenth-second precision with a simple awk command, then graph the result.

It seems interesting that there are spikes at 3.2, 3.5, 4, 4.3, 4.5 seconds. One hypothesis might be that those are individual queries, each warranting its own analysis.

$ head -90000 mysql-slow.log.20120710 \

| fgrep Query_time: \

| awk '{print int($3 * 10)/10}' \

| ~/distribution --verbose --height=30 --char='|o' \

| sort -n

tokens/lines examined: 12,269

tokens/lines matched: 12,269

histogram keys: 481

runtime: 12.53ms

Val|Ct (Pct) Histogram

0 |1090 (8.88%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

2 |1018 (8.30%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

2.1|949 (7.73%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

2.2|653 (5.32%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

2.3|552 (4.50%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

2.4|554 (4.52%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

2.5|473 (3.86%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

2.6|423 (3.45%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||o

2.7|394 (3.21%) ||||||||||||||||||||||o

2.8|278 (2.27%) |||||||||||||||o

2.9|189 (1.54%) ||||||||||o

3 |173 (1.41%) |||||||||o

3.1|193 (1.57%) ||||||||||o

3.2|200 (1.63%) |||||||||||o

3.3|138 (1.12%) |||||||o

3.4|176 (1.43%) ||||||||||o

3.5|213 (1.74%) ||||||||||||o

3.6|157 (1.28%) ||||||||o

3.7|134 (1.09%) |||||||o

3.8|121 (0.99%) ||||||o

3.9|96 (0.78%) |||||o

4 |110 (0.90%) ||||||o

4.1|80 (0.65%) ||||o

4.2|84 (0.68%) ||||o

4.3|90 (0.73%) |||||o

4.4|76 (0.62%) ||||o

4.5|93 (0.76%) |||||o

4.6|79 (0.64%) ||||o

4.7|71 (0.58%) ||||o

5.1|70 (0.57%) |||o

Even if you know sed/awk/grep, the built-in tokenizing/matching can be less verbose. Say you want to look at all the URLs in your Apache logs. People will be doing GET /a/b/c /a/c/f q/r/s q/n/p. A and Q are the most common, so you can tokenize on / and the latter parts of the URL will be buried, statistically.

By tokenizing and matching using the script, you may also find unexpected common portions of the URL that don't show up in the prefix.

$ zcat access.log*gz \

| awk '{print $7}' \

| distribution -t=/ -h=15

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

Art |1839 (16.58%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Rendered |1596 (14.39%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Blender |1499 (13.52%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

AznRigging |760 (6.85%) ++++++++++++++++++++

Music |457 (4.12%) ++++++++++++

Ringtones |388 (3.50%) +++++++++++

CuteStance |280 (2.52%) ++++++++

Traditional |197 (1.78%) ++++++

Technology |171 (1.54%) +++++

CreativeExhaust|134 (1.21%) ++++

Fractals |127 (1.15%) ++++

robots.txt |125 (1.13%) ++++

RingtoneEP1.mp3|125 (1.13%) ++++

Poetry |108 (0.97%) +++

RingtoneEP2.mp3|95 (0.86%) +++

Here we had pulled apart our access logs and put them in TSV format for input into Hive. The user agent string was in the 13th position. I wanted to just get an overall idea of what sort of user agents were coming to the site. I'm using the minimal argument size and my favorite "character" combo of "|o". I find it interesting that there were only 474 unique word-based tokens in the input. Also, it's clear that a large percentage of the visitors come with mobile devices now.

$ zcat weblog-2014-05.tsv.gz \

| awk -F '\t' '{print $13}' \

| distribution -t=word -m=word -c='|o' -s=m -v

tokens/lines examined: 28,062,913

tokens/lines matched: 11,507,407

histogram keys: 474

runtime: 15659.97ms

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

Mozilla |912852 (7.93%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

like |722945 (6.28%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

OS |611503 (5.31%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

AppleWebKit|605618 (5.26%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

Gecko |535620 (4.65%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

Windows |484056 (4.21%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

NT |483085 (4.20%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

KHTML |356730 (3.10%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

Safari |355400 (3.09%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

X |347033 (3.02%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

Mac |344205 (2.99%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

appversion |300816 (2.61%) |||||||||||||||||||||||o

Type |299085 (2.60%) |||||||||||||||||||||||o

Connection |299085 (2.60%) |||||||||||||||||||||||o

Mobile |282759 (2.46%) ||||||||||||||||||||||o

CPU |266837 (2.32%) |||||||||||||||||||||o

NET |247418 (2.15%) |||||||||||||||||||o

CLR |247418 (2.15%) |||||||||||||||||||o

Aspect |242566 (2.11%) |||||||||||||||||||o

Ratio |242566 (2.11%) |||||||||||||||||||o

And here we had a list of referrers in "referrer [count]" format. They were done one per day, but I wanted a count for January through September, so I used a shell glob to specify all those files for my 'cat'. Distribution will notice that it's getting the same key as previously and just add the new value, so the key "x1" can come in many times and we'll get the aggregate in the output. The referrers have been anonymized here since they are very specific to the company.

$ cat referrers-20140* | distribution -v -g=kv -s=m

tokens/lines examined: 133,564

tokens/lines matched: 31,498,986

histogram keys: 14,882

runtime: 453.45ms

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

x1 |24313595 (77.19%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

x2 |3430278 (10.89%) ++++++++

x3 |1049996 (3.33%) +++

x4 |210083 (0.67%) +

x5 |179554 (0.57%) +

x6 |163158 (0.52%) +

x7 |129997 (0.41%) +

x8 |122725 (0.39%) +

x9 |120487 (0.38%) +

xa |109085 (0.35%) +

xb |99956 (0.32%) +

xc |92208 (0.29%) +

xd |90017 (0.29%) +

xe |79416 (0.25%) +

xf |70094 (0.22%) +

xg |58089 (0.18%) +

xh |52349 (0.17%) +

xi |37002 (0.12%) +

xj |36651 (0.12%) +

xk |32860 (0.10%) +

This seems a really good time to use the --logarithmic option, since that top referrer is causing a loss of resolution on the following ones! I'll re-run this for one month.

$ cat referrers-201402* | distribution -v -g=kv -s=m -l

tokens/lines examined: 23,517

tokens/lines matched: 5,908,765

histogram keys: 5,888

runtime: 78.28ms

Val |Ct (Pct) Histogram

x1 |4471708 (75.68%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

x2 |670703 (11.35%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

x3 |203489 (3.44%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

x4 |43751 (0.74%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

x5 |36211 (0.61%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

x6 |34589 (0.59%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

x7 |31279 (0.53%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

x8 |29596 (0.50%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

x9 |23125 (0.39%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xa |21429 (0.36%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xb |19670 (0.33%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xc |19057 (0.32%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xd |18945 (0.32%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xe |18936 (0.32%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xf |16015 (0.27%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xg |13115 (0.22%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xh |12067 (0.20%) ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xi |8485 (0.14%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xj |7694 (0.13%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

xk |7199 (0.12%) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Suppose you just have a list of integers you want to graph. For example, you've captured a "show global status" for every second for 5 minutes, and you want to grep out just one stat for the five-minute sample and graph it.

Or, slightly more-difficult, you want to pull out the series of numbers and

only graph the difference between each pair (as in a monotonically-increasing

counter). The --numonly= option takes care of both these cases. This option

will override any "height" and simply graph all the numbers, since there's no

frequency to dictate which values are more important to graph than others.

Therefore there's a lot of output, which is snipped in the example output that follows. The "val" column is simply an ascending list of integers, so you can tell where output was snipped by the jumps in those values.

$ grep ^Innodb_data_reads globalStatus*.txt \

| awk '{print $2}' \

| distribution --numonly=mon --char='|+'

Val|Ct (Pct) Histogram

1 |0 (0.00%) +

91 |15 (0.05%) +

92 |14 (0.04%) +

93 |30 (0.10%) |+

94 |11 (0.03%) +

95 |922 (2.93%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||+

96 |372 (1.18%) |||||||||||||||||||||||+

97 |44 (0.14%) ||+

98 |37 (0.12%) ||+

99 |110 (0.35%) ||||||+

100|18 (0.06%) |+

101|12 (0.04%) +

102|19 (0.06%) |+

103|164 (0.52%) ||||||||||+

200|62 (0.20%) |||+

201|372 (1.18%) |||||||||||||||||||||||+

202|228 (0.72%) ||||||||||||||+

203|43 (0.14%) ||+

204|917 (2.91%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||+

205|64 (0.20%) |||+

206|178 (0.57%) |||||||||||+

207|90 (0.29%) |||||+

208|90 (0.29%) |||||+

209|101 (0.32%) ||||||+

453|0 (0.00%) +

454|0 (0.00%) +

The Python version eschews the header and superfluous "key" as the Perl version will probably also soon do:

$ cat ~/tmp/numberSeries.txt | xargs

01 05 06 09 12 22 28 32 34 30 37 44 48 54 63 70 78 82 85 88 89 89 90 92 95

$ cat ~/tmp/numberSeries.txt \

| ~/Dev/distribution/distribution.py --numonly -c='|o' -s=s

5 (0.39%) ||o

6 (0.47%) ||o

9 (0.70%) ||||o

12 (0.94%) |||||o

22 (1.71%) ||||||||||o

28 (2.18%) |||||||||||||o

32 (2.49%) |||||||||||||||o

34 (2.65%) ||||||||||||||||o

30 (2.34%) ||||||||||||||o

37 (2.88%) |||||||||||||||||o

44 (3.43%) ||||||||||||||||||||o

48 (3.74%) ||||||||||||||||||||||o

54 (4.21%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||o

63 (4.91%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

70 (5.46%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

78 (6.08%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

82 (6.39%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

85 (6.63%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

88 (6.86%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

89 (6.94%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

89 (6.94%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

90 (7.01%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

92 (7.17%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

95 (7.40%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

$ cat ~/tmp/numberSeries.txt \

| ~/Dev/distribution/distribution.py --numonly=diff -c='|o' -s=s

4 (4.26%) ||||||||||||||||||o

1 (1.06%) ||||o

3 (3.19%) |||||||||||||o

3 (3.19%) |||||||||||||o

10 (10.64%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

6 (6.38%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

4 (4.26%) ||||||||||||||||||o

2 (2.13%) |||||||||o

-4 (-4.26%) o

7 (7.45%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

7 (7.45%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

4 (4.26%) ||||||||||||||||||o

6 (6.38%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

9 (9.57%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

7 (7.45%) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

8 (8.51%) ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||o

4 (4.26%) ||||||||||||||||||o

3 (3.19%) |||||||||||||o

3 (3.19%) |||||||||||||o

1 (1.06%) ||||o

0 (0.00%) o

1 (1.06%) ||||o

2 (2.13%) |||||||||o

3 (3.19%) |||||||||||||o

HDFS files are often rather large, so I first change the numeric file size to megabytes by dividing by 1048576. I must also change it to an int value, since distribution doesn't currently deal with non-integer counts.

Also, we are pre-parsing the du output to give us only the megabytes count and

the final entry in the filename. awk -F / supports that.

$ hdfs dfs -du /apps/hive/warehouse/aedb/hitcounts_byday/cookie_type=shopper \

| awk -F / '{print int($1/1048576) " " $8}' \

| distribution -g -c='-~' --height=20 \

| sort

Key|Ct (Pct) Histogram

dt=2014-11-15|3265438 (2.53%) ----------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-16|3241614 (2.51%) ----------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-20|2964636 (2.29%) ------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-21|3049912 (2.36%) -------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-22|3292621 (2.55%) -----------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-23|3319538 (2.57%) -----------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-24|3070654 (2.38%) -------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-25|3086090 (2.39%) --------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-27|3113888 (2.41%) --------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-28|3124426 (2.42%) --------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-29|3431859 (2.66%) -------------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-11-30|3391117 (2.62%) ------------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-12-01|3167744 (2.45%) ---------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-12-02|3134248 (2.43%) --------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-12-03|3023733 (2.34%) -------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-12-04|3022274 (2.34%) -------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-12-05|3040776 (2.35%) -------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-12-06|3054159 (2.36%) -------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-12-09|3065252 (2.37%) -------------------------------------------~

dt=2014-12-10|3316703 (2.57%) -----------------------------------------------~

The tests directory contains sample input and output files, as well as a

script to verify expected output based on the sample inputs. To use it, first

export an environment variable called distribution that points to the

location of your distribution executable. The script must be run from the tests

directory. For example, the following will run tests against the Perl script

and then against the Python script:

cd tests/

distribution=../distribution ./runTests.sh

distribution=../distribution.py ./runTests.sh

The runTests.sh script takes one optional argument, -v. This enables

verbose mode, which prints out any differences in the stderr of the test runs,

for comparing diagnostic info.

New features are unlikely to be added, as the existing functionality is already arguably a superset of what's necessary. Still, there are some things that need to be done.

- No Time::HiRes Perl module? Don't die. Much harder than it should be. Negated by next to-do.

- Get scripts into package managers.

Perl and Python are fairly common, but I'm not sure 100% of systems out there have them. A C/C++ port would be most welcome.

If you write a port, send me a pull request so I can include it in this repo.

Port requirements: from the user's point of view, it's the exact same script. They pass in the same options in the same way, and get the same output, byte-for-byte if possible. This means you'll need (Perl) regexp support in your language of choice. Also a hash map structure makes the implementation simple, but more-efficient methods are welcome.

I imagine, in order of nice-to-haveness:

- C or C++

- Go

- Lisp

- Ocaml

- Java

- Ruby

- Tim Ellis

- Philo Vivero

- Taylor Stearns