Figure reference: [4]

-

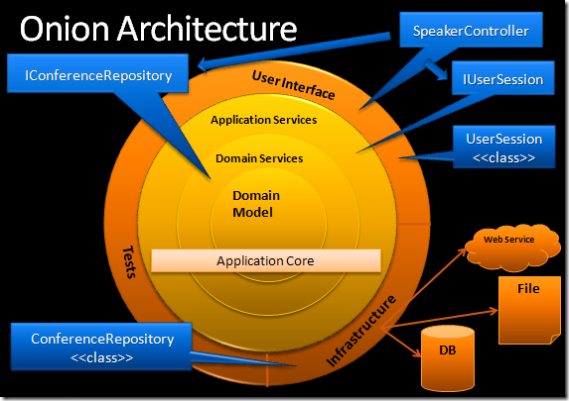

“The diagram to the left depicts the Onion Architecture. The main premise is that it controls coupling. The fundamental rule is that all code can depend on layers more central, but code cannot depend on layers further out from the core. In other words, all coupling is toward the center." [4]

-

"This architecture is unashamedly biased toward object-oriented programming, and it puts objects before all others. In the very center we see the Domain Model, which represents the state and behavior combination that models truth for the organization. Around the Domain Model are other layers with more behavior. The number of layers in the application core will vary, but remember that the Domain Model is the very center, and since all coupling is toward the center, the Domain Model is only coupled to itself." [4]

-

"The first layer around the Domain Model is typically where we would find interfaces that provide object saving and retrieving behavior, called repository interfaces. The object saving behavior is not in the application core, however, because it typically involves a database. Only the interface is in the application core." [4]

-

"Out on the edges we see UI (presentation pattern), Infrastructure (web service, file, DB), and Tests. The outer layer is reserved for things that change often. These things should be intentionally isolated from the application core. Out on the edge, we would find a class that implements a repository interface. This class is coupled to a particular method of data access, and that is why it resides outside the application core. This class implements the repository interface and is thereby coupled to it. The Onion Architecture relies heavily on the Dependency Inversion principle. The application core needs implementation of core interfaces, and if those implementing classes reside at the edges of the application, we need some mechanism for injecting that code at runtime so the application can do something useful. The database is not the center. It is external… Hexagonal architecture and Onion Architecture share the following premise: Externalize infrastructure and write adapter code so that the infrastructure does not become tightly coupled.” [4]

"Key tenets of Onion Architecture:

- The application is built around an independent object model

- Inner layers define interfaces. Outer layers implement interfaces

- Direction of coupling is toward the center

- All application core code can be compiled and run separate from infrastructure" [4]

-

"A common issue to deal with is how to wire together different elements: how do you fit together this web controller architecture with that database interface backing when they were built by different teams with little knowledge of each other. A number of frameworks have taken a stab at this problem, and several are branching out to provide a general capability to assemble components from different layers." [9]

-

"I use component to mean a glob of software that's intended to be used, without change, by an application that is out of the control of the writers of the component. By 'without change' I mean that the using application doesn't change the source code of the components, although they may alter the component's behavior by extending it in ways allowed by the component writers. A service is similar to a component in that it's used by foreign applications. The main difference is that I expect a component to be used locally (think jar file, assembly, dll, or a source import). A service will be used remotely through some remote interface, either synchronous or asynchronous (eg web service, messaging system, RPC, or socket.) I mostly use service in this article, but much of the same logic can be applied to local components too. Indeed often you need some kind of local component framework to easily access a remote service." [9]

class MovieLister{

private MovieFinder finder;

public MovieLister() {

finder = new ColonDelimitedMovieFinder("movies1.txt");

}

public Movie[] moviesDirectedBy(String arg) {

List allMovies = finder.findAll();

for (Iterator it = allMovies.iterator(); it.hasNext();) {

Movie movie = (Movie) it.next();

if (!movie.getDirector().equals(arg)) it.remove();

}

return (Movie[]) allMovies.toArray(new Movie[allMovies.size()]);

}

}

public interface MovieFinder {

List findAll();

}Code Reference: [9]

Figure reference: [9]

-

“... The MovieLister class is dependent on both the MovieFinder interface and upon the implementation. We would prefer it if it were only dependent on the interface, but then how do we make an instance to work with?” [9]. Since 3rd party users may want to use their own implementation like a plugin [10] so no code change is required in MovieLister.

-

"Expanding this into a real system, we might have dozens of such services and components. In each case we can abstract our use of these components by talking to them through an interface (and using an adapter if the component isn't designed with an interface in mind). But if we wish to deploy this system in different ways, we need to use plugins to handle the interaction with these services so we can use different implementations in different deployments. So the core problem is how do we assemble these plugins into an application? This is one of the main problems that this new breed of lightweight containers face, and universally they all do it using Inversion of Control." [9]

-

"In my naive example the lister looked up the finder implementation by directly instantiating it. This stops the finder from being a plugin. The approach that these containers use is to ensure that any user of a plugin follows some convention that allows a separate assembler module to inject the implementation into the lister. As a result I think we need a more specific name for this pattern. Inversion of Control is too generic a term, and thus people find it confusing. As a result with a lot of discussion with various IoC advocates we settled on the name Dependency Injection. I'm going to start by talking about the various forms of dependency injection, but I'll point out now that that's not the only way of removing the dependency from the application class to the plugin implementation. The other pattern you can use to do this is Service Locator…" [9]

-

If you control the flow and when to call methods, you are in control. But when methods are called by system etc… defined by system decision instead of me (I give control to system, so it decides), then I don’t have control. This is inversion of control. [11]

-

Frameworks often use IOC, their methods are called within the framework instead of user invoking each one of them when desired. This is the main difference between framework and library. Libraries have methods, called by users whenever desired, that does some work and returns result and control to the user again. [11]

-

“A framework embodies some abstract design, with more behavior built in. In order to use it you need to insert your behavior into various places in the framework either by subclassing or by plugging in your own classes. The framework's code then calls your code at these points.” [11] (e.g. android framework widgets having listener so you can override and write logic. Then framework invokes your code when listener condition call is met internally).

-

Another example: “So in JUnit, the framework code calls setUp and tearDown methods for you to create and clean up your text fixture. It does the calling, your code reacts - so again control is inverted.” [11]

"The basic idea of the Dependency Injection is to have a separate object, an assembler, that populates a field in the lister class with an appropriate implementation for the finder interface." [9]

Figure reference: [9]

"There are three main styles of dependency injection. The names I'm using for them are Constructor Injection, Setter Injection, and Interface Injection" [9]

There will be some configuration file (of Container, DI library or framework…) to tell which finder implementation with what parameters will be injected here. [9]

public MovieLister(MovieFinder finder) {

this.finder = finder;

}Code Reference: [9]

Again there will be configuration file that wires up right implementation (e.g. Spring framework has this option) [9]

class MovieLister{

private MovieFinder finder;

public void setFinder(MovieFinder finder) {

this.finder = finder;

}

}Code Reference: [9]

Again there will be configuration file that sets up classes, injector and wires the implementations. (e.g. Avalon framework) [9]

public interface InjectFinder {

void injectFinder(MovieFinder finder);

}

class MovieLister implements InjectFinder{

public void injectFinder(MovieFinder finder) {

this.finder = finder;

}

}Code Reference: [9]

"Interface injection is more invasive since you have to write a lot of interfaces to get things all sorted out… My long running default with objects is as much as possible, to create valid objects at construction time. This advice goes back to Kent Beck's Smalltalk Best Practice Patterns: Constructor Method and Constructor Parameter Method. Constructors with parameters give you a clear statement of what it means to create a valid object in an obvious place. If there's more than one way to do it, create multiple constructors that show the different combinations… Another advantage with constructor initialization is that it allows you to clearly hide any fields that are immutable by simply not providing a setter. I think this is important - if something shouldn't change then the lack of a setter communicates this very well. If you use setters for initialization, then this can become a pain. (Indeed in these situations I prefer to avoid the usual setting convention, I'd prefer a method like initFoo, to stress that it's something you should only do at birth.)" [9]

- “The basic idea behind a service locator is to have an object that knows how to get hold of all of the services that an application might need. So a service locator for this application would have a method that returns a movie finder when one is needed. Of course this just shifts the burden a tad, we still have to get the locator into the lister, resulting in the dependencies of figure:” [9]

Figure reference: [9]

-

"ServiceLocator can be Singleton Registry" [9]

-

“I've often heard the complaint that these kinds of service locators are a bad thing because they aren't testable because you can't substitute implementations for them. Certainly you can design them badly to get into this kind of trouble, but you don't have to. In this case the service locator instance is just a simple data holder. I can easily create the locator with test implementations of my services. For a more sophisticated locator I can subclass service locator and pass that subclass into the registry's class variable… A way to think of this is that service locator is a registry not a singleton. A singleton provides a simple way of implementing a registry, but that implementation decision is easily changed.” [9]

Registry: “When you want to find an object you usually start with another object that has an association to it, and use the association to navigate to it. Thus, if you want to find all the orders for a customer, you start with the customer object and use a method on it to get the orders. However, in some cases you won't have an appropriate object to start with. You may know the customer's ID number but not have a reference. In this case you need some kind of lookup method - a finder - but the question remains: How do you get to the finder? A Registry is essentially a global object, or at least it looks like one - even if it isn't as global as it may appear.”

"The important difference between the two patterns is about how that implementation is provided to the application class. With service locator the application class asks for it explicitly by a message to the locator. With injection there is no explicit request, the service appears in the application class - hence the inversion of control… Using dependency injection can help make it easier to see what the component dependencies are. With dependency injector you can just look at the injection mechanism, such as the constructor, and see the dependencies. With the service locator you have to search the source code for calls to the locator… The difference comes if the lister is a component that I'm providing to an application that other people are writing. In this case I don't know much about the APIs of the service locators that my customers are going to use. Each customer might have their own incompatible service locators." [9]

-

An architecture tells us what this system does. “Good architectures scream their intended usage” (e.g. you should be able to open first layer of directory system and everybody should be able to at and say “oh, that is a trading system” or “oh that is an accounting, banking system”…) And you should be able to look at single files and say “ this is where we handle deposits" [2]

-

“When you look at a software system, and you all see is MVC in a web configuration, then the architecture of that system is hiding the use-cases of that system and exposing the delivery mechanism.” … I could dig files and understand from controllers and views that navigation flow of the app but still it is not an architecture, it does not tell me what this system does... I should hunt to know what is the framework, is it web app… Because it is detail and it should be hidden [2]

-

UI is delivery mechanism. “UI should become detail”. [2]

-

"Use cases are delivery independent... It does not care about where the information comes from and it does not care where the information goes. The use case is how the system behaves with its business rules” [2]

-

“Use cases are not controllers or models in MVC” [2]

-

“Interactors have application specific business rules” [2]

-

An architect should defer decisions of databases, frameworks… Because if you decide it right away, you have minimum amount of information to make decision. What database where are going to use? Is this going to be web system? Is this going to be sql or nosql? that is a detail, delay that. “I do not need to start my project with all the tools working”. Important decisions (iteration zero) are VCS, programming language and how to defer other decisions about tools… [2]

-

“A good architecture maximizes the number of decisions not made” [2]

-

“Make delivery mechanism (web, console, mobile) a plugin to your application (use cases, business entities)”… [2]

-

To delay things turn them into plug-in. (e.g.turn database to a plugin) [2]

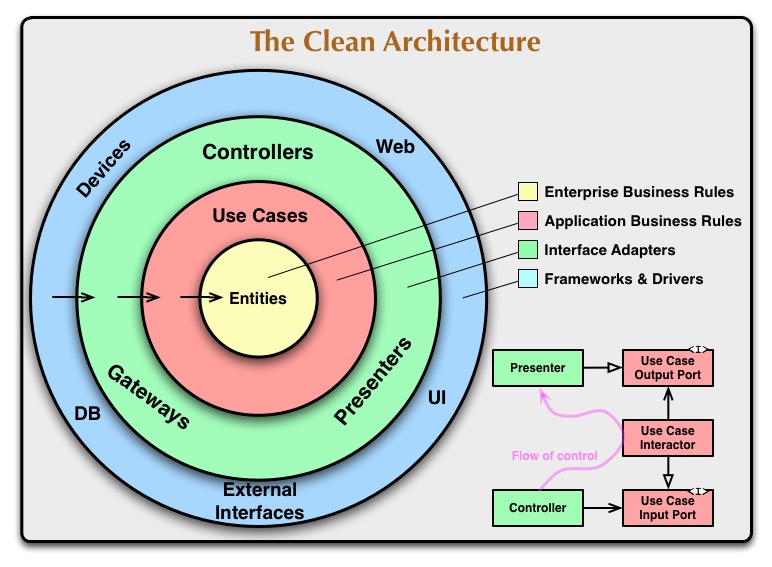

Figure reference: [3]

"Each of these architectures produce systems that are:

-

Independent of Frameworks. The architecture does not depend on the existence of some library of feature laden software. This allows you to use such frameworks as tools, rather than having to cram your system into their limited constraints.

-

Testable. The business rules can be tested without the UI, Database, Web Server, or any other external element.

-

Independent of UI. The UI can change easily, without changing the rest of the system. A Web UI could be replaced with a console UI, for example, without changing the business rules.

-

Independent of Database. You can swap out Oracle or SQL Server, for Mongo, BigTable, CouchDB, or something else. Your business rules are not bound to the database.

-

Independent of any external agency. In fact your business rules simply don’t know anything at all about the outside world." [3]

-

"The outer circles are mechanisms. The inner circles are policies (plan)." [3]

-

"The overriding rule that makes this architecture work is The Dependency Rule. This rule says that source code dependencies can only point inwards. Nothing in an inner circle can know anything at all about something in an outer circle. In particular, the name of something declared in an outer circle must not be mentioned by the code in an inner circle. That includes, functions, classes. variables, or any other named software entity." [3]

-

"By the same token, data formats used in an outer circle should not be used by an inner circle, especially if those formats are generate by a framework in an outer circle. We don’t want anything in an outer circle to impact the inner circles." [3]

"Entities encapsulate Enterprise wide business rules. An entity can be an object with methods, or it can be a set of data structures and functions… If you don’t have an enterprise, and are just writing a single application, then these entities are the business objects of the application. They encapsulate the most general and high-level rules. They are the least likely to change when something external changes…" [3]

"The software in this layer contains application specific business rules. It encapsulates and implements all of the use cases of the system. These use cases orchestrate the flow of data to and from the entities, and direct those entities to use their enterprise wide business rules to achieve the goals of the use case." [3]

"We do not expect changes in this layer to affect the entities. We also do not expect this layer to be affected by changes to externalities such as the database, the UI, or any of the common frameworks. This layer is isolated from such concerns. We do, however, expect that changes to the operation of the application will affect the use-cases and therefore the software in this layer. If the details of a use-case change, then some code in this layer will certainly be affected." [3]

"The software in this layer is a set of adapters that convert data from the format most convenient for the use cases and entities, to the format most convenient for some external agency such as the Database or the Web. It is this layer, for example, that will wholly contain the MVC architecture of a GUI. The Presenters, Views, and Controllers all belong in here…" [3]

"The outermost layer is generally composed of frameworks and tools such as the Database, the Web Framework, etc. Generally you don’t write much code in this layer other than glue code that communicates to the next circle inwards. This layer is where all the details go. The Web is a detail. The database is a detail…" [3]

“…You may find that you need more than just these four. There’s no rule that says you must always have just these four. However, The Dependency Rule always applies. Source code dependencies always point inwards. As you move inwards the level of abstraction increases. The outermost circle is low level concrete detail. As you move inwards the software grows more abstract, and encapsulates higher level policies. The inner most circle is the most general.” [3]

“You can use basic structs or simple Data Transfer objects if you like. Or the data can simply be arguments in function calls. Or you can pack it into a hashmap, or construct it into an object. The important thing is that isolated, simple, data structures are passed across the boundaries. We don’t want to cheat and pass Entities or Database rows. We don’t want the data structures to have any kind of dependency that violates The Dependency Rule.” [3]

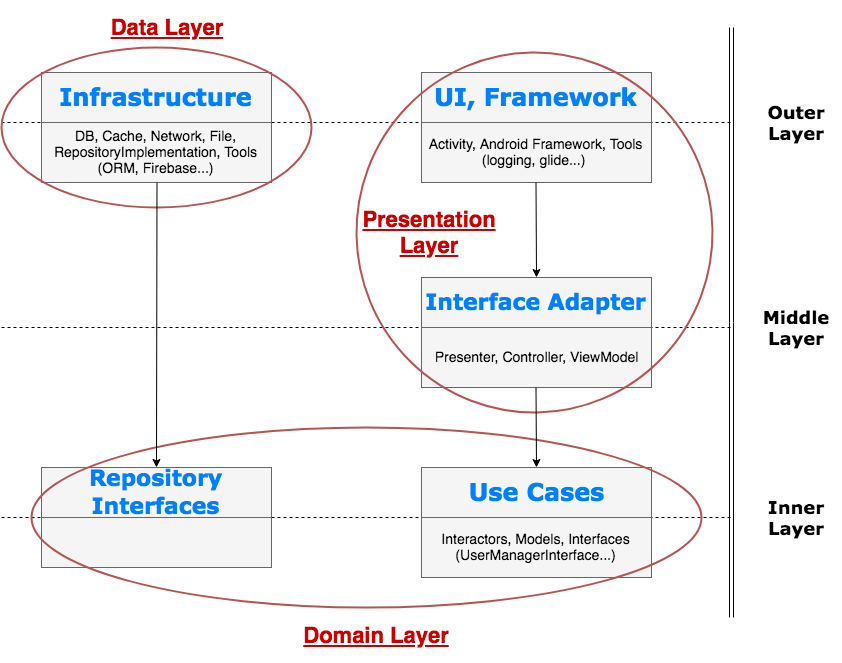

"The general structure for an Android app looks like this:

-

Outer layer packages: UI, Storage, Network, etc.

-

Middle layer packages: Presenters, Converters (mappers)

-

Inner layer packages: Interactors (use cases), Models, Repositories (interfaces only), Executor" [6]

"... this is where the framework details go.

-

UI- This is where you put all your Activities, Fragments, Adapters and other Android code related to the user interface.

-

Storage- Database specific code that implements the interface our Interactors use for accessing data and storing data. This includes, for example, ContentProviders or ORM-s such as DBFlow.

-

Network- Things like Retrofit go here." [6]

"Glue code layer which connects the implementation details with your business logic.

-

Presenters— Presenters handle events from the UI (e.g. user click) and usually serve as callbacks from inner layers (Interactors).

-

Converters— Converter objects are responsible for converting inner models to outer models and vice versa." [6]

"The core layer contains the most high-level code. All classes here are POJOs. Classes and objects in this layer have no knowledge that they are run in an Android app and can easily be ported to any machine running JVM.

-

Interactors— These are the classes which actually contain your business logic code. These are run in the background and communicate events to the upper layer using callbacks. They are also called UseCases in some projects (probably a better name). It is normal to have a lot of small Interactor classes in your projects that solve specific problems. This conforms to the Single Responsibility Principle and in my opinion is easier on the brain.

-

Models— These are your business models that you manipulate in your business logic.

-

Repositories— This package only contains interfaces that the database or some other outer layer implements. These interfaces are used by Interactors to access and store data. This is also called a repository pattern." [6]

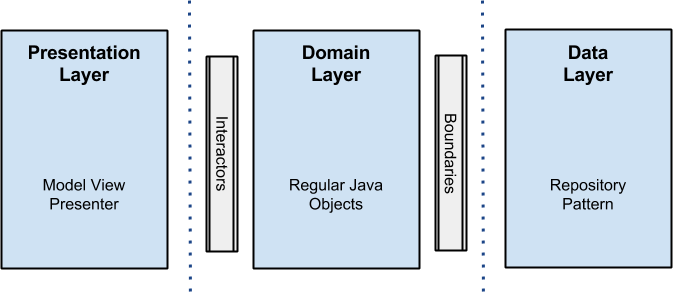

In the Android community, layers above mentioned are not used ("outer layer", "middle layer" and "inner layer"). But instead layers (packages or android modules precisely) below is used.

Figure reference: [5]

- “In here, where the logic related with views and animations happens. It uses no more than a Model View Presenter (MVP from now on), but you can use any other pattern like MVC or MVVM. I will not get into details on it, but here fragments and activities are only views, there is no logic inside them other than UI logic, and this is where all the rendering stuff takes place.” [5]

-

“Business rules here: all the logic happens in this layer. Regarding the android project, you will see all the interactors (use cases) implementations here as well. This layer is a pure java module without any android dependencies. All the external components use interfaces when connecting to the business objects.” [5]

-

"Interactors shouldn’t know anything about Android. There are ways to do threads only using Java, but even Android tools can be used by using dependency inversion. Core can use Android functions via interfaces and dependency injection. Your framework layer can implement an interface with the methods you need in your interactor. You could, for instance, wrap an AsyncTask with a core class, use that core class as the basis of asynchronous calls, and communicate back via Callbacks or an event bus" [1]

-

“All data needed for the application comes from this layer through a UserRepository implementation (the interface is in the domain layer) that uses a Repository Pattern with a strategy that, through a factory, picks different data sources depending on certain conditions. For instance, when getting a user by id, the disk cache data source will be selected if the user already exists in cache, otherwise the cloud will be queried to retrieve the data and later save it to the disk cache. The idea behind all this is that the data origin is transparent for the client, which does not care if the data is coming from memory, disk or the cloud, the only truth is that the data will arrive and will be got.” [5]

-

Unaware of presentation layer but aware of framework, tools...

-

Repository is only way to access and modify the Data. You can add, change, swap data sources in Repository and whoever uses Repository won't be affected. If an Entity can be get from different data sources (network, DB) inside Repository, make DB single source of truth and save data from network in DB and only get data from DB.

Dependency may look like Presentation -> Domain -> Data but it is not correct. To explain layers more in "cleanish" way, this figure is better illustration:

As you can see, it makes sense to separate "Infrastructure" (as in Onion architecture) and "UI, Framework" into different modules (layers) even they stay on same layer in Clean Architecture. "Infrastructure" implements "Repository Interfaces" and "UI, Framework" depends on "Interface Adapters". "Interface Adapters" could be separated in separate module (layer) to force pure java (kotlin) code.

Repository definition: "A system with a complex domain model often benefits from a layer, such as the one provided by Data Mapper (165), that isolates domain objects from details of the database access code. In such systems it can be worthwhile to build another layer of abstraction over the mapping layer where query construction code is concentrated. This becomes more important when there are a large number of domain classes or heavy querying. In these cases particularly, adding this layer helps minimize duplicate query logic. A Repository mediates between the domain and data mapping layers, acting like an in-memory domain object collection. Client objects construct query specifications declaratively and submit them to Repository for satisfaction. Objects can be added to and removed from the Repository, as they can from a simple collection of objects, and the mapping code encapsulated by the Repository will carry out the appropriate operations behind the scenes. Conceptually, a Repository encapsulates the set of objects persisted in a data store and the operations performed over them, providing a more object-oriented view of the persistence layer. Repository also supports the objective of achieving a clean separation and one-way dependency between the domain and data mapping layers" [7]

From the definition above (2nd sentence), repository can have query construction. Also repository is needed when heavy querying is done or too many domain classes. 3rd sentence says it helps to minimize query duplication. It does not say it is the only reason to use Repository. But it helps to achieve this aim (it can hold single addPerson(id) method in repository so everybody uses this method and no addPerson query logic is duplicated). From 6th sentence, you pass the query, parameter, argument declaratively, which means you do not say how you do it (imperative). So it does not have to be sql query! From 8th sentence repository is over data source and abstract it, so domain classes don’t depend on any implementation detail of data source.

[1] A. Leiva, "MVP for Android: how to organize the presentation layer," 15 04 2014. [Online]. Available: https://antonioleiva.com/mvp-android/. [Accessed 14 06 2017].

[2] Robert C. Martin, "Clean Architecture," NDC Conferences (https://vimeo.com/43612849), 2012.

[3] Ubcle Bob (Robert C. Martin), "The Clean Architecture," 13 08 2012. [Online]. Available: https://8thlight.com/blog/uncle-bob/2012/08/13/the-clean-architecture.html. [Accessed 26 02 2018].

[4] Jeffrey Palermo, "The Onion Architecture : part 1," 29 07 2008. [Online]. Available: http://jeffreypalermo.com/blog/the-onion-architecture-part-1/. [Accessed 26 02 2018].

[5] Fernando Cejas, "Architecting Android...The clean way?," 3 09 2014. [Online]. Available: https://fernandocejas.com/2014/09/03/architecting-android-the-clean-way/. [Accessed 26 02 2018].

[6] Dario Miličić, "A detailed guide on developing Android apps using the Clean Architecture pattern," 3 02 2016. [Online]. Available: https://medium.com/@dmilicic/a-detailed-guide-on-developing-android-apps-using-the-clean-architecture-pattern-d38d71e94029. [Accessed 26 02 2018].

[7] Martin Fowler, "Repository," [Online]. Available: https://martinfowler.com/eaaCatalog/repository.html. [Accessed 02 03 2018].

[9] Martin Fowler, "Inversion of Control Containers and the Dependency Injection pattern," 23 01 2004. [Online]. Available: https://martinfowler.com/articles/injection.html. [Accessed 02 03 2018].

[10] Martin Fowler, David Rice, "Plugin," [Online]. Available: https://martinfowler.com/eaaCatalog/plugin.html. [Accessed 02 03 2018].

[11] Martin Fowler, "InversionOfControl," 26 06 2005. [Online]. Available: https://martinfowler.com/bliki/InversionOfControl.html. [Accessed 02 03 2018]

[12] Martin Fowler, "Registry," [Online]. Available: https://martinfowler.com/eaaCatalog/registry.html. [Accessed 02 03 2018]