Streaming is a new protocol of the swarm bzz bundle of protocols. This protocol provides the basic logic for chunk-based data flow. It implements simple retrieve requests and delivery using priority queue. A data exchange stream is a directional flow of chunks between peers. The source of datachunks is the upstream, the receiver is called the downstream peer. Each streaming protocol defines an outgoing streamer and an incoming streamer, the former installing on the upstream, the latter on the downstream peer.

Subscribe on StreamerPeer launches an incoming streamer that sends a subscribe msg upstream. The streamer on the upstream peer handles the subscribe msg by installing the relevant outgoing streamer. The modules now engage in a process of upstream sending a sequence of hashes of chunks downstream (OfferedHashesMsg). The downstream peer evaluates which hashes are needed and get it delivered by sending back a msg (WantedHashesMsg).

Historical syncing is supported - currently not the right abstraction -- state kept across sessions by saving a series of intervals after their last batch actually arrived.

Live streaming is also supported, by starting session from the first item after the subscription.

Provable data exchange. In case a stream represents a swarm document's data layer or higher level chunks, streaming up to a certain index is always provable. It saves on sending intermediate chunks.

Using the streamer logic, various stream types are easy to implement:

- light node requests:

- url lookup with offset

- document download

- document upload

- syncing

- live session syncing

- historical syncing

- simple retrieve requests and deliveries

- swarm feeds streams

- receipting for finger pointing

Syncing is the process that makes sure storer nodes end up storing all and only the chunks that are requested from them.

- eventual consistency: so each chunk historical should be syncable

- since the same chunk can and will arrive from many peers, (network traffic should be optimised, only one transfer of data per chunk)

- explicit request deliveries should be prioritised higher than recent chunks received during the ongoing session which in turn should be higher than historical chunks.

- insured chunks should get receipted for finger pointing litigation, the receipts storage should be organised efficiently, upstream peer should also be able to find these receipts for a deleted chunk easily to refute their challenge.

- syncing should be resilient to cut connections, metadata should be persisted that keep track of syncing state across sessions, historical syncing state should survive restart

- extra data structures to support syncing should be kept at minimum

- syncing is not organized separately for chunk types (Swarm feed updates v regular content chunk)

- various types of streams should have common logic abstracted

Syncing is now entirely mediated by the localstore, ie., no processes or memory leaks due to network contention. When a new chunk is stored, its chunk hash is index by proximity bin

peers syncronise by getting the chunks closer to the downstream peer than to the upstream one. Consequently peers just sync all stored items for the kad bin the receiving peer falls into. The special case of nearest neighbour sets is handled by the downstream peer indicating they want to sync all kademlia bins with proximity equal to or higher than their depth.

This sync state represents the initial state of a sync connection session. Retrieval is dictated by downstream peers simply using a special streamer protocol.

Syncing chunks created during the session by the upstream peer is called live session syncing while syncing of earlier chunks is historical syncing.

Once the relevant chunk is retrieved, downstream peer looks up all hash segments in its localstore

and sends to the upstream peer a message with a a bitvector to indicate

missing chunks (e.g., for chunk k, hash with chunk internal index which case )

new items. In turn upstream peer sends the relevant chunk data alongside their index.

On sending chunks there is a priority queue system. If during looking up hashes in its localstore, downstream peer hits on an open request then a retrieve request is sent immediately to the upstream peer indicating that no extra round of checks is needed. If another peers syncer hits the same open request, it is slightly unsafe to not ask that peer too: if the first one disconnects before delivering or fails to deliver and therefore gets disconnected, we should still be able to continue with the other. The minimum redundant traffic coming from such simultaneous eventualities should be sufficiently rare not to warrant more complex treatment.

Session syncing involves downstream peer to request a new state on a bin from upstream. using the new state, the range (of chunks) between the previous state and the new one are retrieved and chunks are requested identical to the historical case. After receiving all the missing chunks from the new hashes, downstream peer will request a new range. If this happens before upstream peer updates a new state, we say that session syncing is live or the two peers are in sync. In general the time interval passed since downstream peer request up to the current session cursor is a good indication of a permanent (probably increasing) lag.

If there is no historical backlog, and downstream peer has an acceptable 'last synced' tag, then it is said to be fully synced with the upstream peer. If a peer is fully synced with all its storer peers, it can advertise itself as globally fully synced.

The downstream peer persists the record of the last synced offset. When the two peers disconnect and reconnect syncing can start from there. This situation however can also happen while historical syncing is not yet complete. Effectively this means that the peer needs to persist a record of an arbitrary array of offset ranges covered.

once the appropriate ranges of the hashstream are retrieved and buffered, downstream peer just scans the hashes, looks them up in localstore, if not found, create a request entry. The range is referenced by the chunk index. Alongside the name (indicating the stream, e.g., content chunks for bin 6) and the range downstream peer sends a 128 long bitvector indicating which chunks are needed. Newly created requests are satisfied bound together in a waitgroup which when done, will promptt sending the next one. to be able to do check and storage concurrently, we keep a buffer of one, we start with two batches of hashes. If there is nothing to give, upstream peers SetNextBatch is blocking. Subscription ends with an unsubscribe. which removes the syncer from the map.

Canceling requests (for instance the late chunks of an erasure batch) should be a chan closed on the request

Simple request is also a subscribe different streaming protocols are different p2p protocols with same message types. the constructor is the Run function itself. which takes a streamerpeer as argument

The swarm hash over the hash stream has many advantages. It implements a provable data transfer and provide efficient storage for receipts in the form of inclusion proofs usable for finger pointing litigation. When challenged on a missing chunk, upstream peer will provide an inclusion proof of a chunk hash against the state of the sync stream. In order to be able to generate such an inclusion proof, upstream peer needs to store the hash index (counting consecutive hash-size segments) alongside the chunk data and preserve it even when the chunk data is deleted until the chunk is no longer insured. if there is no valid insurance on the files the entry may be deleted. As long as the chunk is preserved, no takeover proof will be needed since the node can respond to any challenge. However, once the node needs to delete an insured chunk for capacity reasons, a receipt should be available to refute the challenge by finger pointing to a downstream peer. As part of the deletion protocol then, hashes of insured chunks to be removed are pushed to an infinite stream for every bin.

Downstream peer on the other hand needs to make sure that they can only be finger pointed about a chunk they did receive and store. For this the check of a state should be exhaustive. If historical syncing finishes on one state, all hashes before are covered, no surprises. In other words historical syncing this process is self verifying. With session syncing however, it is not enough to check going back covering the range from old offset to new. Continuity (i.e., that the new state is extension of the old) needs to be verified: after downstream peer reads the range into a buffer, it appends the buffer the last known state at the last known offset and verifies the resulting hash matches the latest state. Past intervals of historical syncing are checked via the session root. Upstream peer signs the states, downstream peers can use as handover proofs. Downstream peers sign off on a state together with an initial offset.

Once historical syncing is complete and the session does not lag, downstream peer only preserves the latest upstream state and store the signed version.

Upstream peer needs to keep the latest takeover states: each deleted chunk's hash should be covered by takeover proof of at least one peer. If historical syncing is complete, upstream peer typically will store only the latest takeover proof from downstream peer. Crucially, the structure is totally independent of the number of peers in the bin, so it scales extremely well.

The simplest protocol just involves upstream peer to prefix the key with the kademlia proximity order (say 0-15 or 0-31) and simply iterate on index per bin when syncing with a peer.

priority queues are used for sending chunks so that user triggered requests should be responded to first, session syncing second, and historical with lower priority. The request on chunks remains implemented as a dataless entry in the memory store. The lifecycle of this object should be more carefully thought through, ie., when it fails to retrieve it should be removed.

In order to optimize Kademlia load balancing, performance and peer suggestion, we define the concept of address space gap

or simply gap.

A gap is a portion of the overlay address space in which the current node does not know any peer. It could be represented

as a range of addresses: 0xxx, meaning 0000-0111

The proximity order of a gap or gap po is the proximity order of that address space with respect to the nearest peer(s)

in the kademlia connected table (and considering also the current node address). For example if the node address is 0000,

the gap of addresses 1xxx has proximity order 0. However the proximity order of the gap 01xx has po 1.

The size of a gap is defined as the number of addresses that could fit in it. If the area of the whole address space is 1,

the size of a gap could be defined from the gap po as 1 / 2 ^ (po + 1). For example, our previous 1xxx gap has a size of

1 / (2 ^ 1) = 1/2. The size of 01xx is 1 / (2 ^ 2) = 1/4.

In order to increment performance of content retrieval and delivery the node should minimize the size of its gaps, because this

means that it knows peers near almost all addresses. If the minimum gap in the kademlia table is 4, it means that whatever

look up or forwarding done will be at least 4 po far away. On the other hand, if the node has a 0 po gap, it means that

for half the addresses, the next jump will be still 0 po away!.

The current kademlia bootstrap algorithm try to fill in the bins (or po spaces) until some level of saturation is reached.

In the process of doing that, the gaps will diminish, but not in the optimal way.

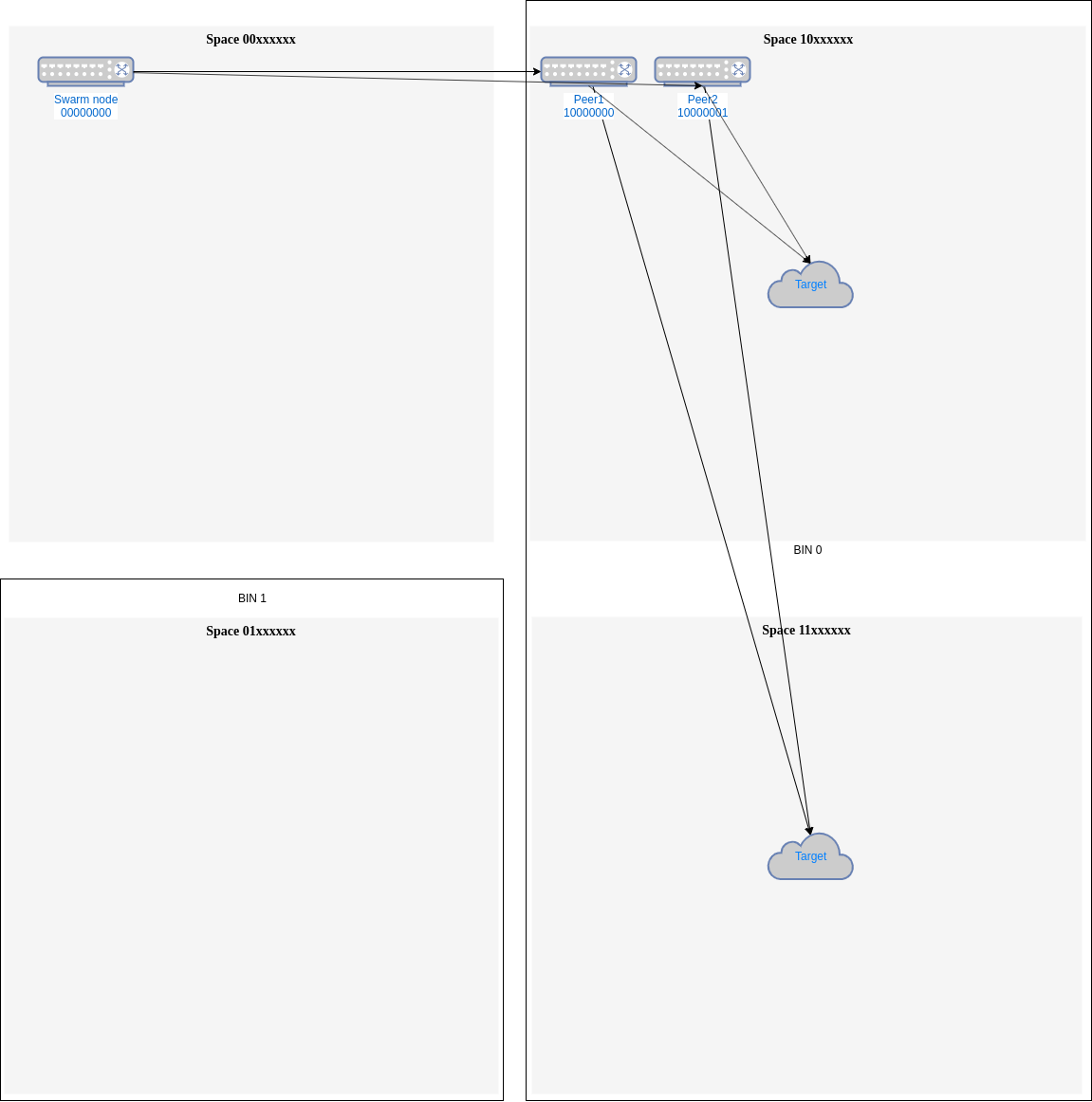

For example, if the node address is 00000000, it is connected only with one peer in bin 0 10000000 and the known

addresses for bin 0 are: 10000001 and 11000000. The current algorithm we will take the first callable one, so

for example, it may suggest 10000001 as next peer. This is not optimal, as the biggest gap in bin 0 will still be

po 1 => 11xxxxxx. If however, the algorithm is improved searching for a peer which covers a bigger gap, 11000000 would

be selected and now the biggest gaps will be po2 => 111xxxx and 101xxxx.

Additionally, even though the node does not have an address in a particular gap, it could still select the furthest away

from the current peers so it covers a bigger gap. In the previous example with node 00000000 and one peer already connected

10000000, if the known addresses are 10000001 and 1001000, the best suggestion would be the last one, because it is po 3

from the nearest peer as opposed to 10000001 that is only po 7 away. The best case will cover a gap of po 3 size

(1/16 of area or 16 addresses) and the other one just po 7 size (1/256 area or 1 address).

One additional benefit in considering gaps is load balancing. If the target addresses are distributed randomly

(although address popularity is another problem that can also be studied from the gap perspective), the request will

be automatically load balanced if we try to connect to peers covering the bigger gaps. Continuing with our example,

if in bin 0 we have peers 10000000 and 10000001 (Fig. 1), almost all addresses in space 1xxxxxxx, that is, half of the

addresses will have the same distance from both peers. If we need to send to some of those address we will need to use

one of those peers. This could be done randomly, always the first or with some load balancing accounting to use the least

used one.

Fig.1 - Closer peers needs an external Load Balancing mechanism

Fig.1 - Closer peers needs an external Load Balancing mechanism

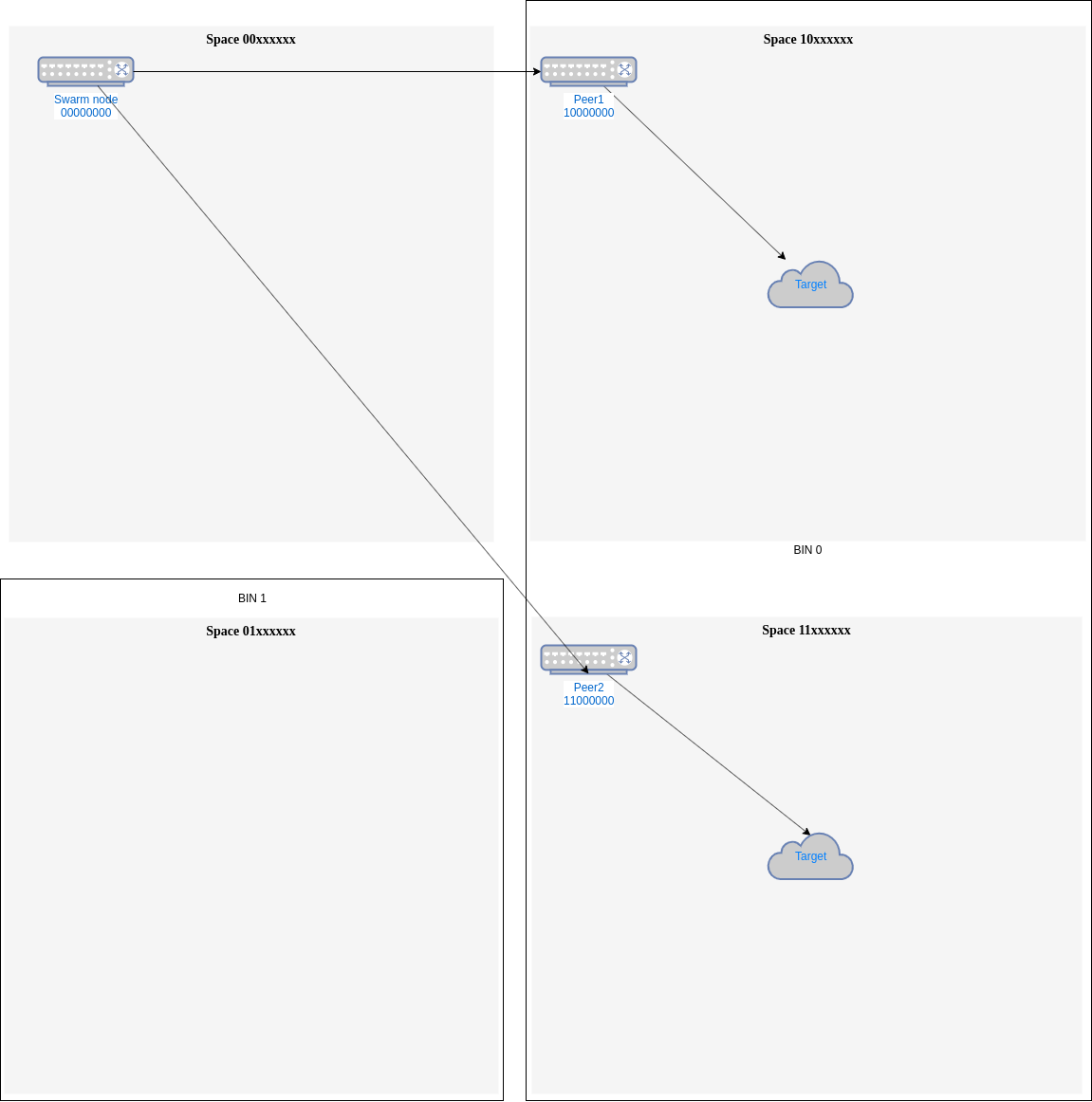

This last method will still be useful, but if the gap filling strategy is used, most probably both peers will

be separated enough that they never compete for an address and a natural load balancing will be made among them (for example,

10000000 and 11000000 will be used each for half the addresses in bin 0 (Fig. 2)).

Fig.2 - Peers chosen by space address gap have a natural load balancing

Fig.2 - Peers chosen by space address gap have a natural load balancing

The search for gaps can be done easily using a proximity order tree or pot. Traversing the bins of a node, a gap is

found if there is some of the po's missing starting from furthest (left). In each level the starting po to search for is the

parent po (not 0, because in the second level, under a node of po=0, the minimum po that could be found is 1).

Implementation of the function that looks for the bigger Gap in a pot can be seen in

pot.BiggestAddressGap. That function returns the biggest gap in the form of a po and

a node under the gap can be found.

This function is used in kademlia.suggestPeerInBinByGap, which it returns a BzzAddress in a particular bin which fills

up the biggest address gap. This function is not used in SuggestPeer, but it will be enough to replace the call to

suggestPeerInBin with the new one.

Instead of the size of a gap, maybe it could be more interesting to see the ratio between size and number of current

peers serving that gap. If we have n current peers that are equidistant to a particular gap of size s,

the load of each of these peers will be on average s/n.

We can define a gap's temperature as that number s/n. When looking for new peers to connect, instead of looking for

bigger gaps we could look for hotter gaps.

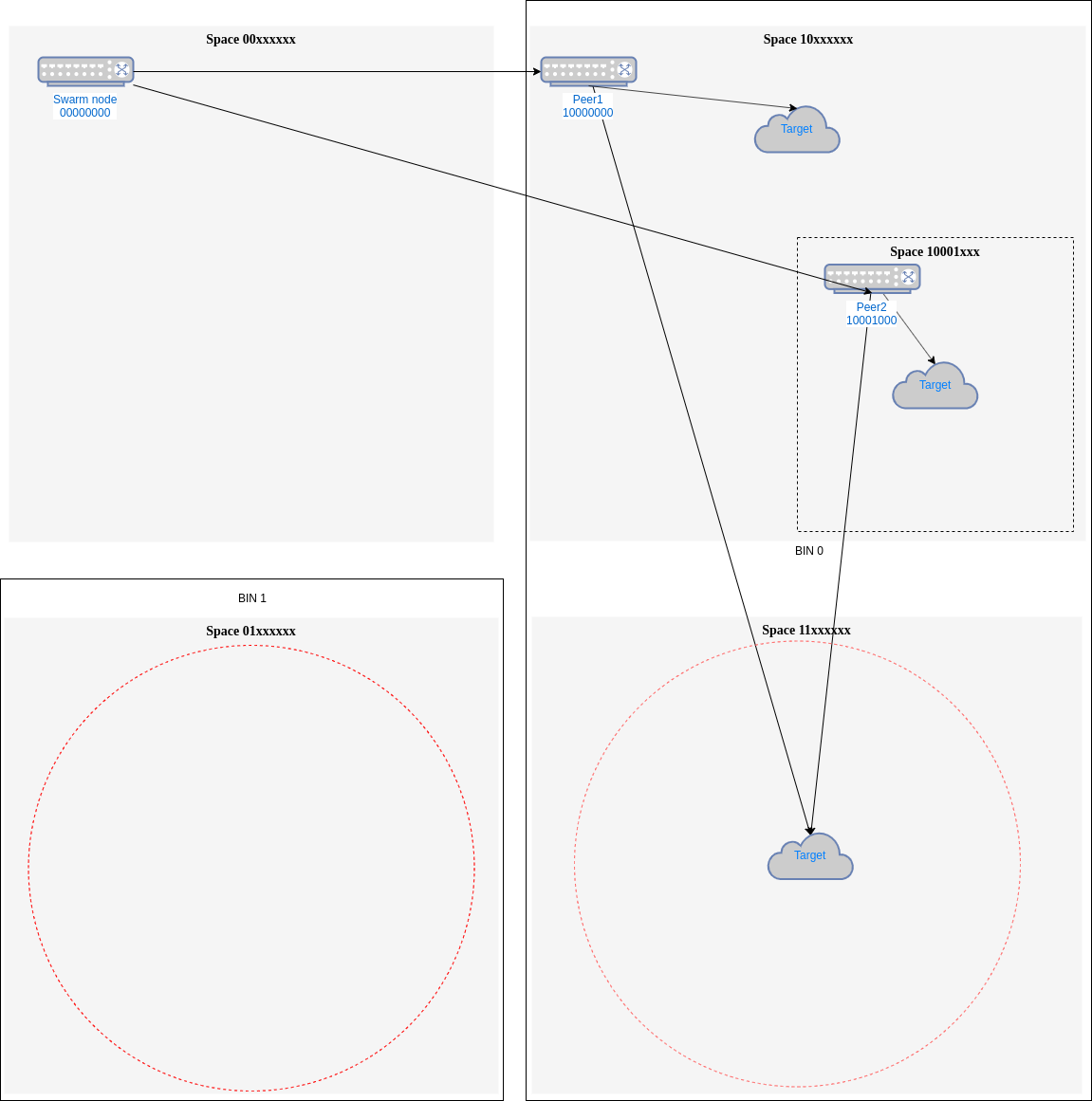

For example, if in our first example, we can't find a peer in 11xxxxxx and we instead, used the best peer, we could end

with the configuration in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 - Comparing gaps temperature

Fig. 3 - Comparing gaps temperature

Here we still have 11xxxxxx as the biggest gap (po=1, size 1/4), same size as 01xxxxxx. But if consider temperature,

01xxxxxx is hotter because is served only by our node 00000000, being its temperature is (1/4)/ 1 = 1/4. However,

11xxxxxx is now served by two peers, so its temperature is (1/4) / 2 = 1/8, and that will mean that we will select

01xxxxxx as the hotter one.

There is a way of implementing temperature calculation so its cost it is the same as looking for biggest gap. Temperature

can be calculated on the fly as the gap is found using a pot.

Other metrics could be considered in the temperature, as recently number of requests per address space, performance of current peers...